African Americans in Las Vegas

Over the course of the twentieth century, economic opportunities encouraged Black migration to the Las Vegas area, but racial discrimination curtailed aspirations for decent employment. Partnership in a ranch attracted John Howell, the first Black man known to own property in Southern Nevada; however the railroad, gaming, and federal projects drew most African Americans to Las Vegas. By 1910, out of the 945 residents of Las Vegas, forty were Black. By mid-century, racism in Las Vegas was so onerous that it had achieved national prominence, causing Nevada to be branded as the “Mississippi of the West.” Over time Black activism and political pressure succeeded in whittling down racial barriers. As of 2008, more than 125,000 Blacks, or at least nine percent of the total population, live and work in the Las Vegas Valley.

Blacks first began to settle in Las Vegas in the spring of 1905 when the fledging town became a stop on the San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad. Most of the men worked as porters and in the railroad repair shop, while women held positions as maids and homemakers. Both sexes shared in entrepreneurial pursuits: owning restaurants, a shoeshine stand, a boarding house, and entertainment venues. Though the town’s water czar, Walter Bracken, encouraged Blacks to live in one particular section of the small town, there was no official policy of segregation, yet Blacks did live on and around Block 17 next to the infamous Block 16 that housed saloons and the red light district. Today this is the downtown area between what are now known as Ogden and Stewart Streets and along Casino Center Boulevard.

The growing Black community fused together because of the forces of racism. In 1924, Elko, Nevada, located in the upper northeastern portion of the state, hosted a Ku Klux Klan march. The Las Vegas demonstration, again in full regalia, transpired the following year. Three years later, the Las Vegas branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), gained a charter and elected Arthur McCants as the first president. Although some historians believe that the KKK activity led to the NAACP formation, it is argued that this 1928 decision was economic in nature, and came as news of the Hoover Dam began to circulate.

The watershed year for the Black community proved to be 1931 when construction began on the Hoover Dam, gambling was legalized, and building plans started on the federal post office/courthouse located on Stewart Street in the heart of the Black community. The number of Black residents grew during the early years of the Great Depression when people poured into the Southern Nevada area seeking work on the Hoover Dam. Simultaneously, many local Blacks pushed out of downtown by the new post office faced restrictive housing covenants and found themselves limited to homes in the “Westside.”

When Blacks were denied jobs on the dam, the community formed the Colored Citizens Labor and Protective Association, an organization that claimed 247 members by September 1931. A negotiator from the NAACP’s regional branch, William Pickens, eventually brokered an end to racial hiring restrictions. Still, although the Black population in Las Vegas had nearly doubled with the promise of work, only forty-four Blacks out of 20,000 workers found jobs on the Dam during its 1931-1935 construction. None of the Black workers were allowed to live in nearby Boulder City, a federal town built to house the Hoover Dam workers.

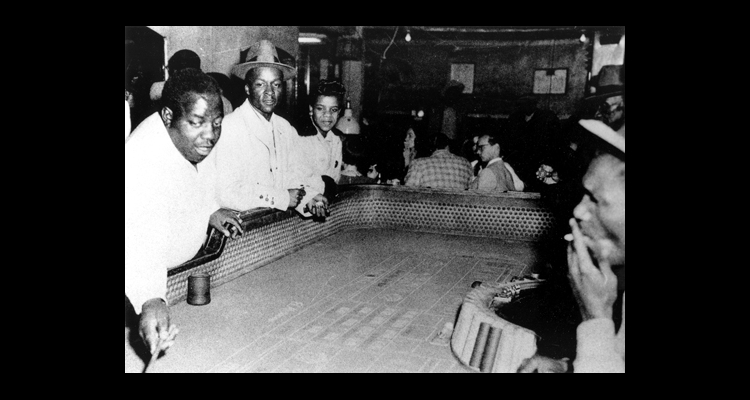

Overt discrimination became a way of life in the forties. Industrial mobilization during World War II not only stimulated additional Black migration, but also contributed to increased racial tension and resulted in widespread segregationist policies in the Las Vegas Valley. The Westside exploded during the war when many Blacks were hired from small towns in the South – especially Fordyce, Arkansas, and Tallulah, Louisiana – to work at Basic Magnesium, Inc., a plant that processed materials to be used for ammunition and airplanes in the war effort. Most of the three thousand or more Blacks that lived in Southern Nevada in 1944 were denied any but the most menial of jobs in casinos and in the plants. All were separated from white patrons in movie theatres and excluded from most restaurants. Casinos did not even allow America’s most famous Black entertainers, including Sammy Davis, Jr., Nat “King” Cole, and Pearl Bailey, to stay where they were performing. Because of these restrictive practices, Black entrepreneurship thrived, and the community formed its own business core on Jackson Street (Avenue) with casinos, restaurants, beauty parlors, barbershops, and other business concerns.

The Westside lagged behind other parts of the city in infrastructure development, planning, and attention by city authorities. Simple amenities such as sewage lines, electricity, and paved streets, that were commonplace in the rest of Las Vegas came slowly, and only at the petitioning of residents. In 1954, the community gained its first housing development, Berkley Square, with homes designed by Black architect Paul Williams and named for a primary financier, Thomas Berkley, a distinguished African American attorney, media owner, and civil rights advocate from Oakland, California.

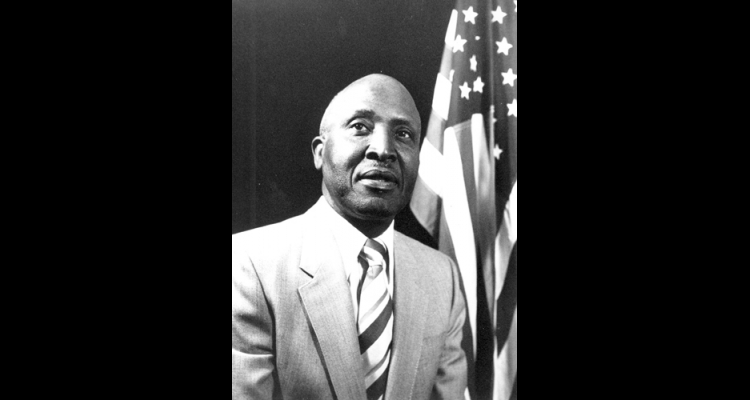

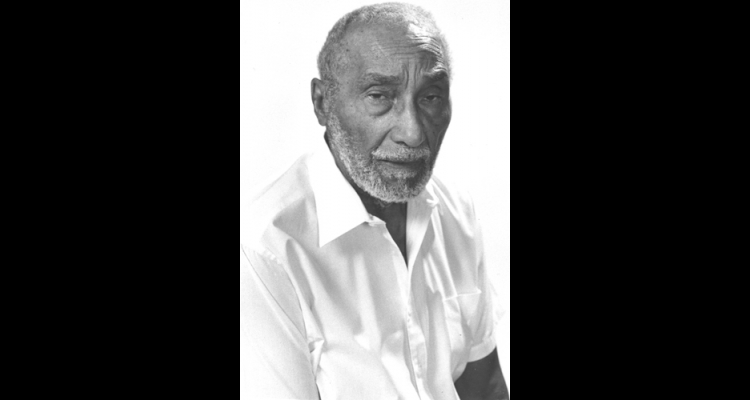

Economically and politically, the Las Vegas Black community expanded rapidly during the 1950s. In 1955, the Moulin Rouge hotel casino, the first integrated upscale establishment in Las Vegas and one that rivaled venues on the Strip and downtown, was built on the outskirts of the Westside. Joe Louis, one of the most famous heavyweight champions in history, served as greeter, the line of black dancers was featured on the cover of Life Magazine, and the nightly crowds were peppered with Hollywood’s elite. After five months of brisk business, the Moulin Rouge closed. Around the same time, Black professionals began to move into Las Vegas in increasing numbers. The first Black doctor licensed by the state of Nevada, Charles I. West, the first Black dentist, James B. McMillan, businessman and entertainer, Bob Bailey, journalist and entertainer, Alice Key, and others, joined long-term residents to improve economic and civil rights in Las Vegas. Those who had been and continued to be engaged in civil disobedience—Mabel Hoggard, the first Black teacher employed by the Clark County School District; J. David Hoggard, executive director of the Economic Opportunity Board (EOB) that brought in thousands of dollars in grant funding for job programs and child care initiatives; Woodrow Wilson, first Black elected to the Nevada State Assembly; Lubertha Johnson, businesswoman, social worker, and the state’s first Black nurse—now enjoyed a heightened level of energy, new ideas, and innovative strategies.

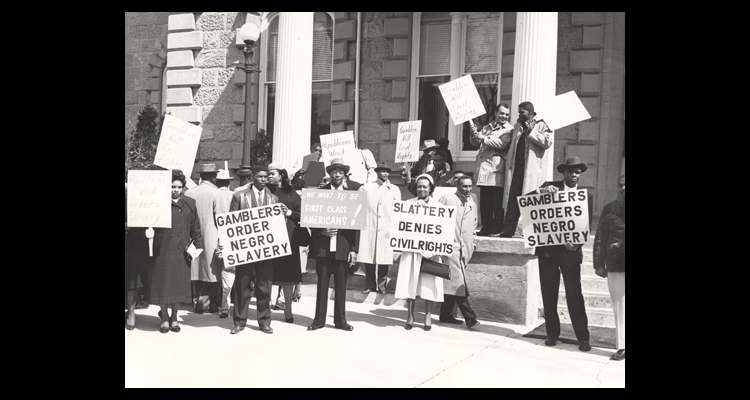

In order to avoid a planned protest march on the Las Vegas Strip, on 26 March 1960, Black community leaders met with elected officials at the once famed Moulin Rouge and reached a verbal agreement to integrate Las Vegas. Newspaper publisher Hank Greenspun chaired the meeting attended by Mayor Oran Gragson, Lubertha Johnson, J. David Hoggard, Donald Clark, Bob Bailey, Dr. James B. McMillan, Dr. Charles I. West, and Governor Grant Sawyer who, as a supporter of civil rights, had received help in his gubernatorial campaign from the Black Nevada Voter’s League. Although no casino industry leaders were present, it is common knowledge that they had approved the deal behind-the-scenes. However, it was in 1971, forced by a United States District Court Consent Decree that Blacks began to work in front-of-the-house positions at elegant gambling locates: Anna Bailey worked as one of the first house dancers at the Flamingo; Faye Todd, Jackie Brantley, and Faye Duncan Daniels were among the first mid-level managers. Jimmy Gay, the city’s first Black mortician from Fordyce, Arkansas, moved up the ranks of the casino industry to become an Assistant Hotel Manager at The Plaza after many years in influential positions at The Sands, and Sarann Knight Preddy, the first Black woman in Nevada to hold a full gaming license, bought the Moulin Rouge in the late 1980s.

Blacks in Las Vegas fought tirelessly for civil and economic equality, gained the right to equal accommodation before the rest of the country, proposed and executed a school desegregation plan, and, led by Ruby Duncan, waged a successful Welfare Rights Movement that included a 1971 march on the Las Vegas Strip. The spirit of those historic battles continues, invigorating ongoing efforts to improve opportunities for economic prosperity, education, healthcare, and housing in ways that benefit not only Blacks, but all of Las Vegas.

Geographic Area: