California Gold Rush

The 1848 discovery of gold in California transformed the West. Over one hundred thousand '49ers immigrated to the Pacific Coast with the Gold Rush. The adventurers became miners and entrepreneurs. Although many successfully pursued diverse opportunities in the unfolding society and economy, few acquired immense wealth.

With a multitude in quest for gold, fortune seekers scattered into every Sierra ravine looking for promising sand bars. These placer miners used inexpensive, easily moved equipment as they exploited one resource after another. A substantial discovery could inspire hundreds if not thousands of others to flood into an area. Opportunists watched for each new rush, understanding that the best chances occurred in the opening days of a mining district. Still, most places that caused excitement in the 1850s disappointed the majority.

Nevada's history of mining dates to a discovery directly related to the California Gold Rush. In 1849, Abner Blackburn was traveling to California through northwest Nevada when he discovered gold near the juncture of the Carson River and a ravine that would soon be called Gold Canyon. Word of his discovery inspired a backwash of California placer miners to travel over the Sierra.

Beginning in 1850, several hundred miners worked valuable deposits in Gold Canyon. There, the settlement that would be called Dayton became their home base. Although distance separated these settlers from the core of the California Gold Country, they were part of the Gold Rush. Like their neighbors to the west, they worked deposits that had accumulated over the millennia.

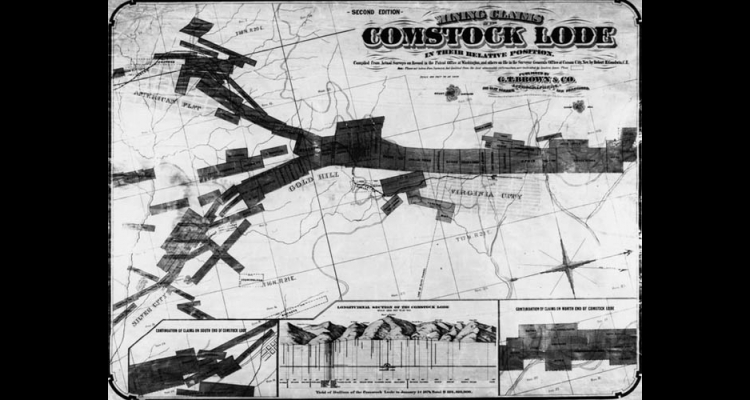

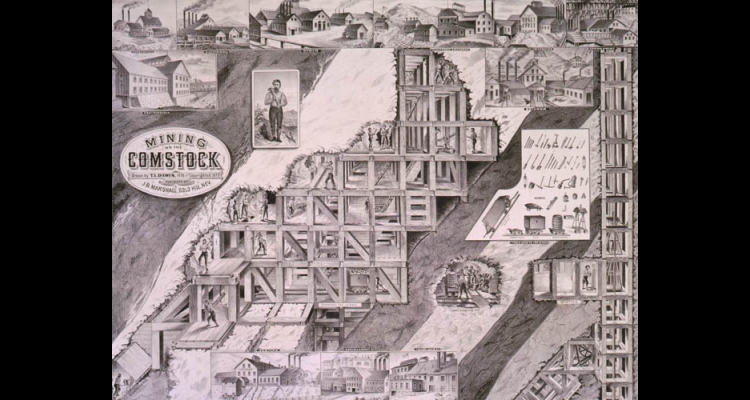

Following the pattern elsewhere, placer miners depleted the Gold Canyon sands. By the late 1850s, many left to look for new opportunities, just as they had in the California gold fields. A few miners explored the mountain above, and their strikes in 1859 opened a new chapter for the West. The 1859 discovery of the Comstock Lode at Virginia City set off yet another rush. This event, however, contrasted with 1849, providing a second bookend for the period, framing the decade. The Rush to Washoe, a reference to a term for the region, drew many '49ers who still hoped to acquire true wealth. Like elsewhere, only the first few acquired valuable claims for little money.

Still, because the Comstock yielded such large ore bodies, it employed thousands for several decades. With a minimum of four dollars for eight hours underground, the Comstock offered the best wages in the industrial world, thanks largely to a strong union.

Diehard optimists continued their quest for wealth throughout the West, opening the region for future settlement and development, but after 1859, the expectations of the majority were permanently changed. For most, the idea of striking it rich by discovering a valuable claim yielded to the ambition of earning a good wage and, if the opportunity presented itself, of raising a family in a wholesome community. Many still dreamt of sudden wealth, but gambling with stocks became the most common outlet for this hope. The stock market, however, like placer mining, rarely proved profitable.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.

Further Reading

None at this time.