Charcoal Burner's War of 1879

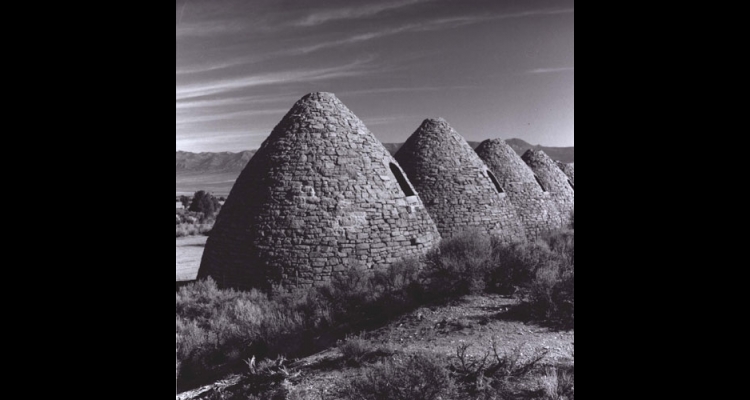

In 1879, the so-called Charcoal Burners War pitted Italian charcoal burners against companies that bought and used the product. During the 1870s, hundreds of Italians and Swiss immigrants (many Italian speaking) settled in the newly emerging Eureka Mining District. Many of these arrivals brought an Alpine tradition of slowly burning logs in an oxygen-starved environment to produce charcoal. The Eureka mills processed stubborn ore, which required charcoal because it burned at a higher temperature than wood. The immigrants consequently had a market for their talent.

Unfortunately, the foreign charcoal burners, working in small groups scattered in the hillsides, became easy targets for exploitation. Companies that purchased the charcoal for sale to the smelters often paid in scrip that could only be spent in their stores, featuring over-priced essentials. Teamsters frequently understated the amount of charcoal actually received, so they could take their own cut of the profits. In addition, the charcoal burners consumed hundreds of acres annually, denuding the nearest hills and requiring them to exploit increasingly remote stands of trees. This increased their costs. By 1874, the hills around Eureka were denuded for a twenty-mile radius. Within four years, the blighted zone had expanded to fifty miles around the mining center. Consumption of the forests destroyed roughly 5,000 acres per year. While costs of charcoal production inflated, the amount paid actually decreased as a result of the coordinated efforts of smelter owners and the merchants who procured and delivered the material.

In July 1879, approximately five hundred immigrants formed the Charcoal Burners' Protective Association to demand a fair price for the charcoal. Prosperous Italian merchants in Eureka initially lent support. Lambert Molinelli, for example, was a successful business owner who served as vice president of the Association. What began as a peaceful effort to improve the lot of immigrants, however, soon became violent. The Association advocated striking and refused to allow teamsters to load charcoal sold by non-union burners. The Eureka County sheriff sent out posses to arrest agitators, with only limited success. Hundreds of angry immigrants controlled the hillsides. As the labor movement became increasingly confrontational, support from local Italian businessmen evaporated and Molinelli among others resigned from the Association.

Confrontation escalated until August 11 when the sheriff and the Eureka County commission won support from Governor John Kinkead with his activation of the Second Brigade of the Nevada Militia, stationed in Eureka. Throughout this period, the sheriff made several arrests, but most charcoal burners were law abiding, while resolute in preventing charcoal from being delivered. The situation reached a climax on August 18 when deputies confronted a large number of burners at Fish Creek, south of Eureka. Accounts differ, but it is clear the deputies killed five immigrants (three Italians and two Swiss Italians) and wounded several others. No deputies were injured.

At this point, the Italian and Swiss consulates in San Francisco and Italian-speaking immigrants throughout the West took up the cause of the workers. Inquests failed to reach a conclusion regarding what actually happened, so no one was imprisoned. The sheriff dropped charges against incarcerated immigrants. At the same time, local mining slumped, reducing the need for charcoal. Much of the inspiration for the trouble subsequently decreased. Many immigrants left Eureka County as the economy worsened, while others remained.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.

Further Reading

None at this time.