Circus Circus

When Jay Sarno designed his Caesars Palace hotel-casino, which opened on the Las Vegas Strip in 1966, he envisioned it as a center of Ancient Roman extravagance. His next idea for a casino had less appeal to big gamblers, but was just as ambitious–he wanted it to house the largest circus in the world. Sarno's Circus Circus became another pop culture symbol closely associated with Las Vegas. It remained a famous, if gaudy and kitschy, attraction on the Strip for more than four decades.

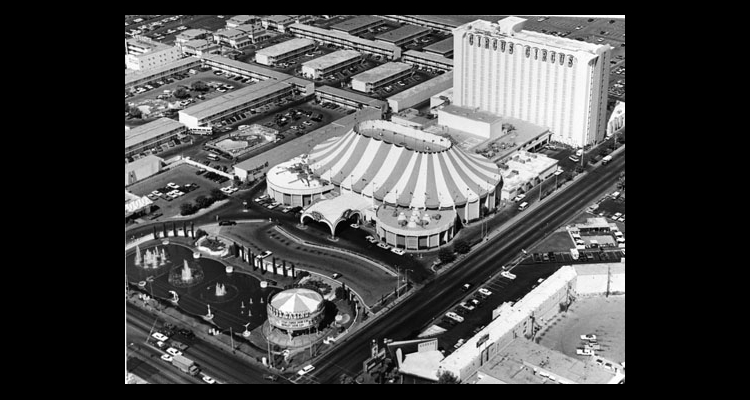

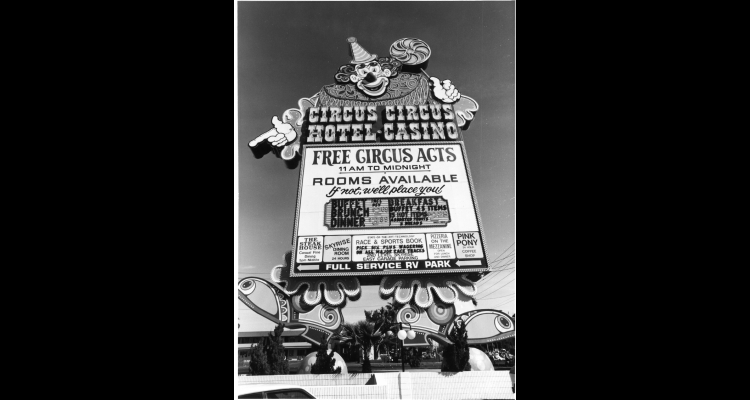

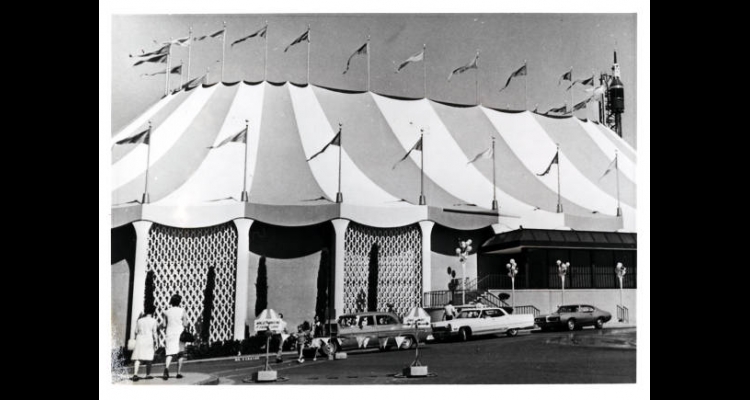

Sarno, with partners from Georgia and Texas, and a loan from the Teamsters Union Central States Pension Fund, spent $15 million developing Circus Circus as a working casino inside a "big-top" building shaped like a pink and white circus tent. Acrobats and trapeze artists performed live shows high over the table games and slot machines. To keep the kids away from the casino, as required by Nevada law, Sarno built a circular midway on the second floor, overlooking the casino, with carnival-type games and space to watch the circus performers.

The Circus Circus casino, across from the Riviera and Thunderbird hotels, debuted without any hotel rooms–during a live broadcast of the Ed Sullivan Show, a popular television variety program, on October 18, 1968.

Unlike Caesars Palace, which was an immediate hit, Sarno's new project suffered business losses thanks to some of his atypical management decisions. In a first for Strip casinos, Sarno charged customers small admission fees to enter the casino while the circus acts performed. He dropped them when the public objected. A circus elephant he bought to throw craps dice, play keno, and pull a slot machine handle with its trunk startled patrons and spread offensive odors inside the property. Once, an aerialist fell down onto a gambling table, prompting the hotel to install a large safety net.

While other Las Vegas casinos had catered to adults with children in minor ways, Sarno's Circus Circus was regarded as the first to market directly to family vacationers, although he also sought big spending gamblers. Others, viewing the Strip as a classy place best reserved for well-dressed adults, criticized Sarno's entire approach. One was billionaire Howard Hughes, who had started acquiring Strip hotels in the late 1960s. Hughes wrote to an aide: "The aspect of this circus that has me disturbed is the popcorn, kids side of it. In other words, the poor, dirty shabby side of circus life. The dirty floor, sawdust and elephants."

Sarno's casino did not produce the revenues he had projected and in 1969, under pressure from the Nevada Gaming Control Board, he resigned to allow one his executives to operate the casino. That year, the casino opened the Hippodrome showroom, featuring circus arts, magicians, and nude dancer revues.

Sarno returned in early 1970 and in 1971. He attracted new financing in the form of a loan of $2.6 million from the Teamsters pension fund, which was controlled by organized crime associates James "Jimmy" Hoffa, the union's president, and Allen Dorfman. The loan gave the pension fund control of the land the Circus Circus was built on, but the union leased it back to Sarno's casino company. The pension fund also gave Sarno a loan of $15.5 million that year, and another $2.6 million in 1972, the year Circus Circus opened its first hotel rooms inside a 400-room, fifteen-floor tower.

Business improved at the hotel-casino until the national gasoline crunch of the early 1970s started to reduce auto traffic to Las Vegas. Losing large sums of money from month to month in 1974, Sarno opted to unload Circus Circus by leasing the casino to two business executives, William Bennett (a former Del Webb gaming executive) and William Pennington. Bennett and Pennington made significant changes to Sarno's approach, gearing the hotel more to budget and mid-level gamblers, taking out some of Sarno's carnival games, and concentrating on making the midway a profitable business. Sarno served as an advisor and was permitted to remain living at the hotel, inside a fancy suite. Under his supervision, Circus Circus finished another fifteen-story hotel tower in 1975.

Sarno became the source of trouble again for Circus Circus, this time involving allegations of skimmed casino profits and secret investments by organized crime leaders based outside of Nevada. By 1977, the Teamster pension fund, regarded as corrupted by organized crime, had at Sarno's request lent Circus Circus a total of $26 million. Federal investigators said that Sarno served as a "front man," allowing secret skimming of casino proceeds by mob interests in Chicago connected to the union pension fund.

In 1979, former Circus Circus casino executive Carl Thomas admitted his participation in a scheme to skim cash for hidden organized crime interests. Meanwhile, a Chicago organized crime member, Anthony Spilotro, had operated a jewelry store near the midway at Circus Circus, and federal and Nevada law enforcement officials learned he was in charge of the Chicago mob's skimming operation at the casino there.

Amid the controversies, Circus Circus expanded to include a recreational vehicle park in 1979 and five low-rise hotel buildings in 1980. In 1983, Bennett and Pennington cashed out Sarno and took the casino company public. Now called Circus Circus Enterprises, the corporation sold shares on Wall Street and raised investment money through stock sales. Growing flocks of tourists in the 1980s made Circus Circus one of the most successful Las Vegas casinos ever. Budget-minded travelers liked its low-priced, no-frills rooms, inexpensive buffets, elaborate wedding chapel, and well-respected gourmet steak house.

In 1986, the Circus Circus company expanded its casino and debuted a new twenty-nine-story tower, with nearly 1,200 hotel rooms. Another 1,000-room tower opened in 1993, as did the $90 million Adventuredome, an enormous, glassed indoor amusement park with a roller coaster and other rides and carnival games, located in the rear of the property.

The flow of cash from the casino and its investors on Wall Street provided Circus Circus Enterprises with the resources to build two major Strip hotel-casinos, the Excalibur in 1990 and the Luxor in 1993, after which Bennett resigned from the company. Continuing to build on the success of the Circus Circus and its other properties, the company opened the Monte Carlo in partnership with Steve Wynn's Mirage Resorts in 1996.

In 1999, the firm was renamed the Mandalay Resort Group, and opened the Mandalay Bay Hotel-Casino on the southern end of the Strip, the site of the former Hacienda hotel. It remained highly successful under the management of a onetime Bennett protege, Glenn Schaeffer. Six years later, the Las Vegas gaming company MGM Mirage, owner of the MGM Grand Hotel, acquired Mandalay Resort Group, including Circus Circus, in a more than $8 billion deal.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.

Further Reading

None at this time.