Comstock Mining Folklore

Miners possess their own oral traditions, beliefs, jargon, and customs. Mineral wealth also inspired folklore outside the occupation. Legends of lost mines, for example, belong to the general population. In contrast, only miners normally shared concerns about whistling underground or harming rats in mines. While many have studied western mining folklore, little has been done in Nevada.

Western mines attracted people from throughout the world. Nevada's mixture of diverse cultures yielded complex folklore. Because mining established communities that could disappear in a matter of months or years, its oral traditions and customs assumed many forms in various places and over time.

Other aspects of the occupational folklore were widespread in the West. Mining folklore included special words used throughout the industry. Some terms transcended the labor force and emerged in common use. "Lode," for example, is a Cornish word for ore body. "Bonanza" is Spanish for a valuable deposit. "Borrasca," the impoverished antithesis of bonanza, found equal use in the nineteenth-century West. Comstock miners were known as "hot water plugs" after the chronic problem of suddenly-erupting scalding subterranean water.

Miners often believed spirits dwelt in the eerie underground environment. In Nevada, these were often ghosts of dead miners. The prominence of Cornish immigrants caused their belief in Tommyknockers, underground elves, to influence others. As a result, mine spirits sometimes took this name and had elfish traits.

While some European traditions survived in the West, others did not. Miners in Nevada set aside the Old World prohibition against women underground. Historical documents describe frequent mine tours given to guests of both genders, a practice that would have evacuated an excavation in many parts of Europe.

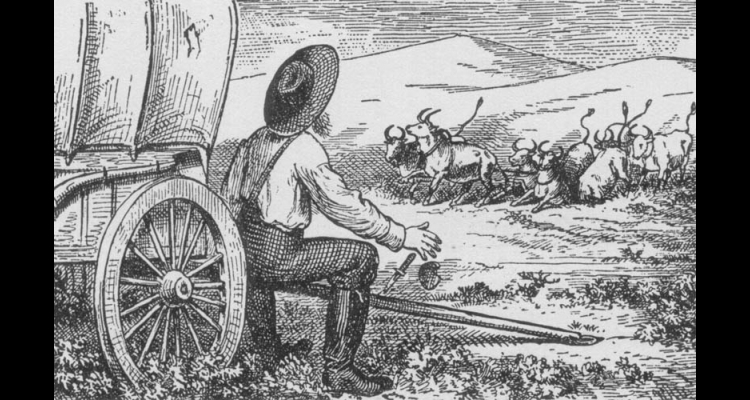

Stories of goats and oxen falling into shafts were common, but the donkey is probably the most important animal in western mining folklore. In Nevada, donkies were called Washoe or desert canaries. A Comstock legend told of a Washoe zephyr lifting a Washoe canary, braying in fright as it sailed above town. A well-known story has a donkey wander away from a prospector's camp. The frustrated owner, often fighting an illness, pursues the animal, and in his wandering, finds an outcropping of ore. This, for example, appears in the account of the discovery of the Mizpah Ledge near what would become Tonopah.

In folklore, the truth of the story is not as important as its repetition. Historical legends may be based on reality. Mining barons such as James Fair and John Mackay easily slipped into oral tradition. A widespread tale also involves a woman who arrived early in a district's development, enabling her to profit from wise or lucky investments. The woman becomes a millionaire, and whether she succeeded remarkably or lost everything, local oral traditions hold these characters with particular fascination. The Comstock's Eilley Orrum Bowers filled this role.

The western tradition of the tall tale inspired writers to repeat and exaggerate local legends. Dan De Quille's The Big Bonanza (1876) is particularly rich with contemporary folklore. Unfortunately, it and other sources can only hint at what was certainly a rich body of belief and oral tradition associated with mining.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.

Further Reading

None at this time.