Eureka

The Eureka Mining District began with a few claims staked in 1864. Initially, miners sent limited silver ore to Austin mills. By 1866, new discoveries attracted more attention, but the presence of lead made milling the silver ore difficult.

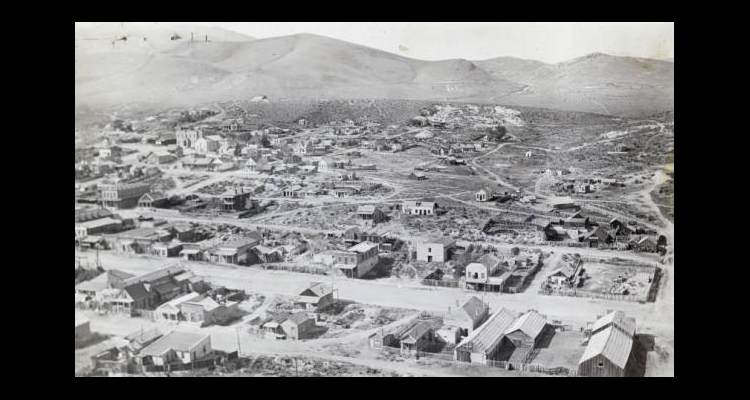

In 1869, Colonel G. C. Robbins constructed a draft furnace specifically designed for Eureka's ore, opening the door for development. By the end of the year, about one hundred people had settled in the canyon, eventually naming their town Eureka. This was the time of the White Pine Excitement, so young Eureka looked east to neighboring Hamilton for regional leadership. With the failure of that town, Eureka assumed the role of a satellite community of Austin.

Unlike most boom-and-bust mining communities, Eureka enjoyed steady, gradual growth as mine production remained unremarkable but consistent. In 1870, the Eureka Sentinel, a newspaper that enjoyed a long prosperous history, began printing. Three years later, Eureka became the seat of Eureka County, breaking ties with Austin and Lander County.

In 1875, the narrow gauge railroad, the Eureka and Palisades, connected the town to the transcontinental railroad to the north. Throughout the 1870s, unsubstantiated claims characterized the population as growing to nearly nine thousand people. The 1880 federal census, however, more accurately reported only about forty-two hundred people living there. Still, it was a substantial mining community. Cautious county commissioners waited until then to build a courthouse, an imposing $53,000 Italianate structure. It survives as one of two Nevada nineteenth-century courthouses that continue to serve local government in their original capacities, the other being Virginia City's Storey County courthouse.

Fires devastated Eureka several times during the 1870s, but it was always able to rebuild. Mine production remained consistent and prosperity persisted.

One of Eureka's more infamous incidents involved the violent suppression of local charcoal burners. Charcoal was a key ingredient to local milling. Italian and Swiss immigrants worked in forests surrounding Eureka, and in 1879, they went on strike when mill owners reduced payments for charcoal. Armed forces suppressed the union activity, and the "war" resulted in several deaths.

By the mid 1880s, miners had nearly depleted Eureka's ore bodies. Larger mines persisted in exploration and the processing of meager ore, but by the early 1890s the mines closed. Many people left for better prospects. Still, limited discoveries in the early twentieth century led to brief periods of activity.

In the 1980s, Eureka became the hub of regional modern gold mining. At the same time, Eureka County enjoyed the benefit of taxes from gold mining in the enormous, fabulously rich Carlin Trend to the north. Workers lived in Elko County, which was deprived of most of the industry's tax revenue, leaving tiny Eureka County with public funds but little need to provide services. The windfall supported community projects including the restoration of the Eureka Opera House, now one of the finest nineteenth-century structures of its kind to survive in the West.

Article Locations

Related Articles

Further Reading

None at this time.