Gareth Hughes: Unlikely Missionary to the Paiutes

In May 1958, Reno and San Francisco newspapers announced that Gareth Hughes, Welsh-born silent screen celebrity and Shakespearean stage actor, was leaving his mission to Pyramid Lake Paiute Indians and returning to his homeland. The widespread and richly deserved praise for nearly two decades of tireless dedication to Nevada Indians was also punctuated with mysteries, theological controversies, and issues of personal identity. When he left Nevada, he carried with him a lung disease contracted in the course of his ministry. He returned to Southern California before succumbing to the disease and arranged for Reno to be his final resting place.

Hughes was born William John Hughes at Llanelli, Wales, on August 23, 1894. As a promising child actor he was allowed to join a troupe of Welsh actors in London, England, at the age of seventeen. A few years later the group had an unsuccessful tour in New York, but Hughes stayed on and soon appeared in a variety of roles at the New Amsterdam Theatre, among others. He assumed the stage name of Gareth—a common Welsh baby name meaning “gentle.” After several years on stage, he made his first movie in 1918, having moved to Hollywood, California. He returned to Paramount Studios on Long Island, New York, in 1921 to star in Sentimental Tommy, a film that enjoyed some success.

On February 1, 1922, famous director and actor William Desmond Taylor was murdered in his Hollywood home. Among the numerous suspects was Gareth Hughes, who was questioned by the police and released. None of the suspects was ever arrested and the case was considered unsolved until 1964, when actress Margaret Gibson, a.k.a. Patricia Palmer, confessed to the murder on her deathbed. Hughes's career was unaffected by the investigation, and he appeared in more than forty films through 1931. Cecil B. DeMille dubbed him a “young idealist,” popular writer Fulton Oursler called him a “charm boy,” a female actress considered him the best of dancers, and William J. Mann's serious study of Hollywood personalities characterized him in his younger days as a “flaming little queen.” He was five feet seven inches tall, with brown hair and blue eyes, and a boyish face that placed him in casting parts reserved for much younger men. He played opposite the stars of the silver screen, including Rudolph Valentino and Marion Davies, who became a lifelong friend. Like many gay men of his era, he attempted to mask his sexual orientation by dating women.

At the height of his silent film career, Hughes was earning as much as $2,000 per week. The stock market crash and subsequent Depression wiped out Hughes's accumulated wealth, and he returned to acting in a Work Projects Administration program making $94 a month. In the late 1930s he became director of the Los Angeles Federal Theatre, specializing in religious and Shakespearean productions. He directed and starred in the educational film Shakespeare the Immortal, which was sold to schools for $35 per print in 1940. It was about this time that Hughes made a sudden career change.

He entered the Protestant Episcopal Monastery of the Society of St. John the Evangelist in Cambridge, Massachusetts. As a postulant of this religious order (at one time called the Cowley Fathers), it is said he first assumed the title “Brother David” after the patron saint of Wales. He remained less than a year before—according to one of Gareth's interviewers—he entered the Anglican Benedictine monastery of the Holy Cross at West Park, New York, staying until 1942.

At this time, the Protestant Episcopal Church in Nevada was in the throes of finding pastoral leadership for its far-flung missions and churches. Bishop William F. Lewis turned to members of the Holy Cross monastery for assistance. Father Karl Tiedemann, O.H.C (Order of the Holy Cross) became vicar at the Pyramid Lake Paiute Reservation's Episcopal church of St. Mary's in Nixon, Nevada, with attendant duties at Wadsworth and Fernley. Not coincidentally, Gareth Hughes had determined that monastic life at Holy Cross was not his permanent calling, and he responded to an invitation from Bishop Lewis to serve as a “lay reader and missionary” to the Paiute Indians at the Fort McDermitt Indian Reservation in fall of 1942. It was the site of tiny St. Anne's Episcopal Church, where lay missionary Alice Wright had begun serving Paiutes and their white neighbors in nearby McDermitt in 1932, with Deaconess Clara Orwig following in 1941.

This reservation on the remote northern border of Humboldt County was subject to severe weather. Hughes recalled that the winters were so harsh that his 1921 Studebaker could be “encased in ice up to its hubcaps.” Fortunately, the romantic companion of William Randolph Hearst, Marion Davies, gave her old silent screen friend Gareth Hughes a Cadillac. However, the luxury vehicle was unable to negotiate the rugged Nevada terrain, and Hughes gave it up for something more practical, knowing she would understand. Hughes was accorded special treatment when he later visited San Simeon, California, and Hearst Castle, where he was welcomed to stay at Davies Guest House.

During his tenure at McDermitt, Gareth Hughes appears to have taken some time away to get himself ordained in about 1946. According to several unrelated sources, Hughes was ordained in the Apostolic Episcopal Church in 1945. This church was founded in 1925 as a protest against certain Protestant Episcopal and Anglican tenets of belief and practice and was regarded as a rogue sect. Hughes continued to refer to himself as “brother” rather than “father,” and his ordination as an Episcopal minister by this group appears to have been officially unrecognized or simply overlooked by Nevada Protestant Episcopal authorities. Bishop Lewis praised Brother David's work with the McDermitt Paiutes “under the most incredible difficulties” as “superb.” A decade later Hughes observed to an interviewer that he used his stagecraft to “act out” scriptural messages to make them more understandable to his Indian charges. The fruit of his labors was evident. Writing to a family member in Wales in 1948, he recounted that tiny St. Anne's Church was “packed every Sunday” with worshippers coming by horseback from ten miles distant. “When I have the Holy Communion there isn't enough room to hold them,” he continued, providing some personal testimony that he may have functioned briefly in what he perceived to be a priestly role.

During his pastoral work, Brother David rarely used his professional name of Gareth Hughes, as when he authored an article on “Medieval Religious Drama” for the Missionary District of Nevada publication The Desert Churchman, published in January 1945. He also engaged in public debate and subsequent controversy through the pages of the national Protestant weekly, the Christian Century. Herbert J. Mainwaring was a High Church Episcopal layman, who sparred with anyone disparaging the Church's Catholic origins. In a 1947 letter to the editor of the Christian Century, Hughes had offended the conservative leanings of Mainwaring, who subsequently published a letter in the June 15 edition of Nevada's Desert Churchman. Hughes responded with a letter written in Wadsworth to Mainwaring chastising him for criticizing the word “Protestant” in the Protestant Episcopal Church's official title. Mainwaring responded immediately to “Mr.” Hughes, denigrating his ordination in “a little sect in the mid-West.” Hughes, he wrote, had abandoned the Episcopal Church's Catholic roots by becoming ordained as a “minister,” thereby (in Mainwaring's eyes) disassociating himself from the Episcopal Church. Hughes, however, remained a valued asset to the Protestant Episcopal Church in Nevada.

Because of his successes with Native Americans in McDermitt, Bishop Lewis transferred Brother David to the larger Paiute Indian Reservation at Nixon. There he introduced himself in the services record book with a challenge to Mormon proselytizers, with whom he had apparently crossed swords at McDermitt. “The scourge of Moroni, Brother David,” he wrote, “came on Friday Aug. XIX 1949.” From time to time during his tenure at Nixon, he recorded in the church record book his criticism of Mormon-sponsored events, such as a dance on Good Friday in 1953.

He regularly commuted back to McDermitt, 250 miles away, and also served the nearby Union Church of Wadsworth and Fernley. Occasionally, he was asked to preach or preside at a funeral at the Walker River Indian Reservation south of Fallon, and as far away as Gardnerville and Austin. St. Mary's Church records at Nixon show that Brother David presented forty-three persons for confirmation to Bishop Lewis from 1950 to 1954 and that he presided over seventy-three burials and baptized fifty-three individuals from 1949 to 1955. He held regular Sunday and holy day services, morning prayer, and evening prayer, but the records indicated that visiting priests, rather than Brother David, presided over Holy Communion. Although Brother David's services routinely attracted three to four times more participants than those led by visiting clergy, he was not functioning as an ordained Episcopal priest during his stay at Nixon.

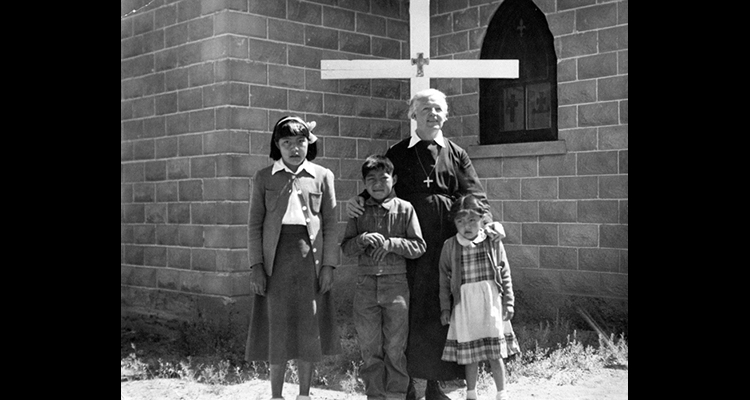

Wearing the garb of the Order of the Holy Cross, Brother David became a beloved icon of Christian care—interested in the Indians' spiritual salvation as well as their material welfare. He appealed to his Southern California friends for financial assistance to the Indians and even begged for a “small Jeep” from Louis B. Mayer through their mutual friend, University of Nevada professor Charlton Laird. Brother David found no task too menial. He mentioned to friends that he often cleaned up the results of leaky papooses. He maintained and remodeled the church at Nixon and regularly sorted donated clothing in its crypt. This practice eventually contributed to his declining health.

Brother David became a celebrated local hero and a celebrity who was featured in magazine articles and newspapers across the country. Fulton Oursler dubbed him a “star in the desert.” Reno columnist Ty Cobb reported that he was not above serving as ring announcer for an amateur boxing match sponsored by the Pyramid Lake Paiute Indians. His cultured Welsh accent stood in marked contrast to the ensuing pugilistic warfare between contestants Robert “Frenchy” Laxalt, Moe Macias, and Jack Swobe, who became local celebrities themselves. Reno newspapers consistently referred to him as a “priest” or the “beloved rector,” though in the eyes of his bishop he was simply a lay missionary with an ordination outside the traditional Episcopal Church. His oratorical skills and ability to motivate young people led to his preaching the baccalaureate address at Fernley High School for ten successive years—continuing well after he left the church at Nixon.

Effective June 1, 1955, Bishop Lewis appointed Father Joseph Hogben to be resident priest at St. Mary's, Nixon, and reassigned Brother David back to St. Anne's, McDermitt. The Nixon parish record book noted in his handwriting on that date: “The end of seven years service as a glorified janitor in the Lord's service—who ran not away from Mormons neither left his Indian charges. Alleluia!”—to which Father Hogben added: “God bless you & God love you Brother David!”

He served McDermitt for a year but was forced to retire on doctor's orders due to a worsening lung disease, byssinosis, caused by lint inhaled from the used clothing he laundered and sorted at Nixon. He continued to maintain his residence at Wadsworth, where he stored his collection of very valuable sixteenth- and seventeenth-century books and manuscripts. These works were exhibited in Reno in spring of 1956, before he donated them, with some religious vestments, to the University of Nevada library's special collections. After Brother David's retirement from McDermitt, the English department chairman, Robert Gorrell, invited him to teach a course in dramatics at the university and described him as “very knowledgeable” and “very skillful,” but not particularly well organized. Hughes also directed rehearsals of plays, and, at least occasionally, wore clerical garb. For about eighteen months he was affiliated with Reno's Park Wedding Chapel, where he presided at the marriage of former Nixon parishioners, among others, and of Virginia Fletcher and celebrated writer Erskine Caldwell on New Year's Day 1957.

Brother David, the missionary and sometime wedding chapel employee, abandoned his religious title for his stage name, Gareth Hughes, by which he had referred to himself in correspondence even while serving as a missionary. In 1958 he returned to Wales, expecting to end his days in the homeland. His lungs longed, however, for the dry and sunny climate of Southern California. He visited old friends in Hollywood and soon after retired to the Motion Picture Country House and Hospital in Woodland Hills, where he functioned as an unofficial chaplain to its residents, many of whom he knew well. He maintained a correspondence with dozens of families and former students from Nixon and McDermitt and invariably included in his letters a small amount of money to those whom he knew to be in need. Professor Charlton Laird and his wife, Helen, visited Hughes through 1964, by which time he was regularly requiring oxygen.

He died October 1, 1965, at Woodland Hills and by prearrangement was buried at Mountain View Cemetery in Reno. In death he was still fondly remembered and greatly missed by his many former parishioners, in whose service he spent, as he often wrote, his “happiest days” and which service he considered his “greatest privilege.”

Article Locations

Related Articles

Further Reading

None at this time.