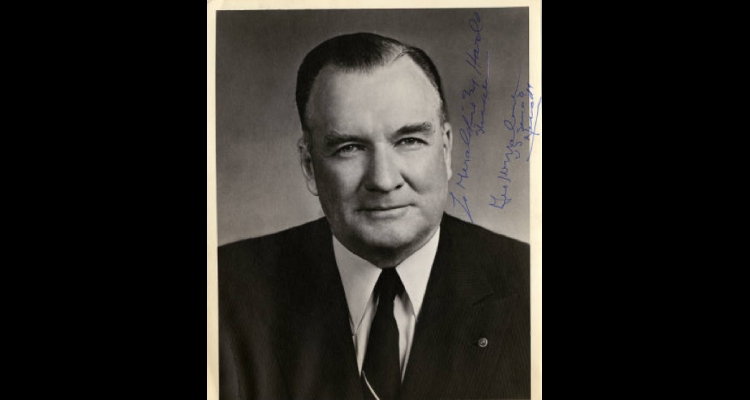

George Malone

Although not highly regarded during his lifetime, Nevada politician George Malone has endured as a champion of conservative causes. He is quoted on right wing web sites on everything from free trade to the Korean armistice. Born August 7, 1890, in Fredonia, Kansas, Malone graduated from the University of Nevada in 1917, and then enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War I, rising from private to lieutenant in two years. Malone served as Nevada state water engineer during Governor Fred Balzar's administration (1927-1935).

After several unsuccessful attempts to secure a congressional seat, Malone won election to the U.S. Senate against Berkeley Bunker in the pivotal 1946 election. According to historian Steven Wagner, "The 'Class of 1946,' as the first-term Republicans were called, was dominated by members of the conservative 'old guard' who were eager to overturn as much New Deal legislation as possible..."

Malone voted for the Taft-Hartley Act and other touchstones of conservative faith. He endorsed a greatly weakened Equal Rights Amendment in a wire to the Reno Republican Women's Club on August 20, 1953, decades before the amendment became a political hot button. Malone also tended to local matters, such as a bill he cosponsored with U.S. Senator Alan Bible allowing the city of Henderson to purchase 7,000 acres of federal land to accommodate growth. President Eisenhower signed the measure on May 14, 1956. In addition, Malone actively promoted atomic power, forming a committee on July 23, 1952, chaired by former state engineer Alfred Merritt Smith, to work for installation of the first atomic power plant at Ruby Hill near Eureka, Nevada.

Malone became a reliable vote for conservative orthodoxy in the Senate of the 1950s, but on matters with less cultural or symbolic meaning, Democratic floor leader Lyndon Johnson could capture his vote. According to columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak, Malone's undistinguished personality left him out of the flow of things in the Senate. Johnson, seeing his isolation, cultivated Malone and was able to win his vote occasionally.

The Evans and Novak description of Malone as a "crashing bore" is not unique. The New York Times once reported that Malone was capable of emptying the Senate chamber merely by rising to address the chair. A similar description of "a Western senator" in Tom Wicker's novel, Facing the Lions, put Malone's lackluster reputation into popular culture.

Malone was reelected in 1952, thanks in large measure to a crippling split in the Democratic Party over the candidacy of upstart Thomas Mechling, who defeated party favorite Alan Bible in a bruising primary election. Malone's involvement with extreme conservative elements in the GOP threatened his relationship with the party's more moderate figures. In October 1956, the problem blew up in Malone's face. President Eisenhower described Malone, Joseph McCarthy, and William Jenner as three Republican senators he could not count on, adding that they had "little place" in the GOP. Nevada's lone member of the House, Malone's fellow Republican Cliff Young, agreed, telling the Mineral County Independent, "It is a fact Senator George Malone has opposed and voted against many policies of the Eisenhower administration—even more so than Senator Joseph McCarthy." (Young later denied making the comment, but the Independent stood by the quote.)

In 1958, a much weakened Malone faced a strong Democrat, Howard Cannon, and no party split aided Malone this time. Cannon easily defeated him. He made another race for the House in 1960, losing to Democrat Walter Baring. Malone remained in Washington and died there on May 19, 1961.

Article Locations

Related Articles

Further Reading

None at this time.