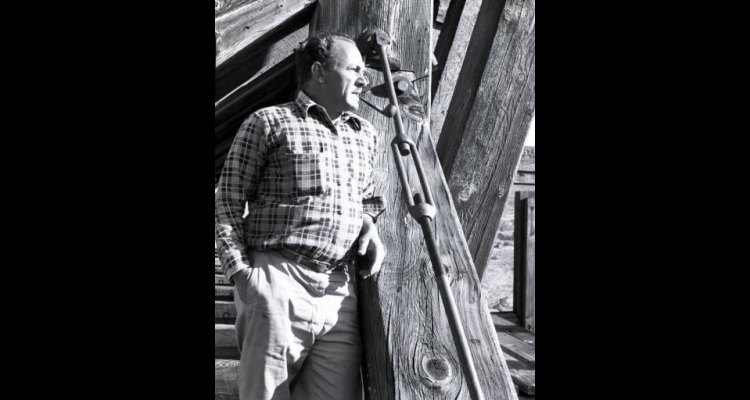

Gus Bundy

Gus Bundy settled in Nevada in 1941 after spending his youth in New York City; during his twenties Bundy traveled widely, both as a seaman aboard a U.S. Navy vessel, and as an art and curio collector in Japan in the late 1930s. Professionally, Bundy was a photographer as well as an accomplished painter and sculptor. In 1957, he participated in the founding of a portrait workshop in Northern Nevada that is active to this day. His photographs are archived in Special Collections in the University of Nevada, Reno library.

Below is reprinted with permission from the Nevada Historical Society Quarterly.

Nevada Historical Society Quarterly

Volume 33, Summer 1990, Number 2

Ahmed Essa

GUS BUNDY(1907-1984)

Gus Bundy was a highly complex person and hence difficult to understand. His tendency to brood, for instance, gave the impression that he was a loner. He had the habit of contemplating, certainly, but isn't it characteristic of an artist to be constantly deep in thought? In any case, Bundy had lots to think about, especially his past. He was fortunate to have had a rich life, an asset for an artist.

Everyone who met him found him intriguing. Part of his complexity consisted of a series of contradictions. He talked and lived like a native Nevadan, and yet he was a native New Yorker, born and reared and educated in Manhattan and Long Island. He looked serene and settled, and yet he was a wanderer, an adventurer; and his idea of making a home with his new bride was to live in China during World War II. He roamed the deserts and mountains of Nevada as though a thorough westerner at heart, and yet one of his major influences was the Orient and his most treasured possession a collection of Oriental art, mainly Japanese.

August Bundy was born in New York City in 1907, a member of a large family. His father had a violent temper and made Gus suffer. This, too, is an asset for an artist, for it is now axiomatic that an unhappy childhood makes for greater creativity in later life. In Gus Bundy's case, it also made him more aware of human relationships, and he responded, both as an artist and as a teacher and a caring person. He demonstrated this awareness as early as high school. A fellow student, now a practicing physician in New York, recalls an incident of forty years ago when a bully threatened their mutual friend. Gus, the physician said, "very quietly but effectively called his bluff and put the bully in his place."

A teacher at the high school, impressed by Bundy's art work, recommended him for an opening at the Brooklyn Museum Art Students League. That was the beginning of Bundy's career as an artist. Another break occurred when he had the opportunity to attend the Grand Central School of Art. It was at this school that Bundy met the person who most influenced him: Arshile Gorky, described by an art historian "as the direct link between the European surrealist painters and the painters of the U.S. Abstract Expressionist movement." The classes Bundy attended were filled with violin music because Gorky wanted his students to express their feelings in their drawings. Bundy also had the added advantage of being singled out to accompany Gorky to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bundy became a teacher early in his career. He taught at the Lincoln School of Art and, remarkable for so young an artist, at the New School of Social Research. The New School, in its Bulletin No.5 of 1931, described his course as a design workshop, where the work "will be freely creative in any possible medium." The tuition was $6.00 a month.

Despite these promises of a successful artistic career and a growing reputation as a photographer in New York City, where he shared a studio with a friend, Bundy decided to give in to a wanderlust. In 1927 he worked as a seaman on the SS Aryan. He returned to Manhattan and during the Depression decided on a whim to wander around Mississippi. A severe bout of malaria put an end (temporarily, as it later turned out) to his travels.

The ensuing period was productive. His paintings were exhibited at the New York No-Jury Exhibition Salons at The Forum in Rockefeller Center in 1934, and a year later he guided youthful artists at the Boys' Club of the Navy Yard District in Brooklyn in painting "nautical murals" on the walls of the club's auditorium. Toward the end of the same year, according to a report in the New York World-Telegram, the Kamin Bookshop was "featuring the linoleum cuts of Bundy" in that season's original and "unusual Christmas cards."

Financially, it must have been a difficult period. In 1937 Bundy did a stint as a reporter for the Brooklyn Eagle. Two years later he was off to Japan, buying curios and shipping them back to the United States.

It was in Kobe in 1940 that he met and married Jeanne Amberg, a young Swiss woman who had been born in Japan and was still living there. The marriage changed his life in more ways than one. It made him seriously consider where he would permanently live. When Jeanne was expecting a baby, he decided New York City was no place to raise a child. He preferred the remote area where he had visited a friend in 1939 on his way to Japan: Washoe Valley, Nevada.

He settled there in 1941, even though it was only a small house and garage, without electricity or adequate water. The setting was both scenic and historical. The Sierra was the backyard, and the place had once been the town of Ophir, the ore mill of the Comstock.

He was one of the very few artists then living in Northern Nevada. "Artists were regarded as very strange," he recalled in a 1980 interview. What made it more difficult for him to fit into his new surroundings was his additional interest in theater. Nevertheless, it was home, although during this period he spent some time serving the military in Maine, photographing a series of tests of winter gear that the army carried out.

By the time he moved to Nevada, he had developed skill in a variety of artistic endeavors. For him, painting was first, then photography. As his wife Jeanne put it, "He was in a sense a Renaissance Man—not content with just one form of creative expression. He painted, sculpted, made jewelry, did photography and worked with wood. He built things—he was fascinated with the process of creation."

Early on, he set himself a challenge: to thrust the work of art from its two-dimensional limit of paper or canvas and give it a heightened reality. The solution he came up with is evident in his drawing exercises. They consist of pages and pages of curves. For him, the curve made the line dynamic, giving it energy and movement. Its finest rendition is in the depiction of a flock of seagulls converging upon food on a dock, rendered primarily in the sweeping curves of their wings.

He also found the curves useful in painting abstractions. The most prominent features of his two outstanding abstractions—Sunlight and Tree Trunks and Dark Movement toward Light—are curves.

Although he found nature most attractive—another reason for settling in Nevada—his primary interest was in people. They dominate most of his art work—the sculpture and carvings, but especially the drawings, paintings, and photographs. What emerges in those three media is Bundy's ability to go beyond simple portraiture and delineate the personality of the subject, whether it is a laborer or fisherman in Mexico or a friend in Carson City. He continued to paint portraits into his later years, but whatever the technique—impressionistic brush strokes or meticulous realism—the individuality of the subject comes through.

The only technique Bundy tried but did not pursue is Chinese brush painting. This is all the more surprising because in the few examples that he did, his strokes demonstrate that he had exceptional skill in wielding the brush. In the traditional practice exercises, for example, depicting a bamboo stalk or a curved leaf, Gus does apply the right pressure at the appropriate places.

Bundy's presence made an enormous difference to the art world of Northern Nevada. He was always part of the nucleus of some group or another. He had an affinity for and was drawn to all creative people, not just artists. The group that met in the old brewery in Virginia City included such writers as Walter Van Tilburg Clark and Roger Butterfield. (Bundy wrote poetry, too.) Bundy, in fact, remembered fondly an art gallery on the main street of Virginia City. Later, he organized a portrait workshop which continued to function for more than two decades until he and Marge Means were the only remaining members of the original group.

His presence also made a difference in the attitudes toward wild horses. The photographs he took of horsemeat hunters rounding up the horses made the world aware of how cruelly they were treated. Not only did his pictures help convince lawmakers in Washington, D. C., to strengthen measures to protect the horses, but they were published in many parts of the world for more than thirty years.

Bundy's private self has remained undisturbed, which is as it should be, with one exception. To complete this biographical sketch, mention must be made of his sense of humor, which often saved the day. When he bought sixteen boxes of Tide detergent at a bargain price, and Jeanne said that there was no room in their house to store them, he quipped, "The ship hasn't come in, but the Tide has."

"Misfortune is opportunity," he said when things were going badly. And they often did. Which is why his summing up of his life in Nevada should be taken as a compliment. He said that he "has been successful here."

Article Locations

Related Articles

Further Reading

None at this time.