Howard Hughes

Howard Robard Hughes, Jr. was the reclusive billionaire, airline owner, aviator, government contractor, and film producer who would have a major impact on the future of Las Vegas after moving there in 1966. By the late 1960s, he owned six casinos on the Las Vegas Strip as well as other hotel-casinos and businesses around the state. Hughes was determined to rid Las Vegas of its ties to organized crime. His presence brought credibility to casino gambling as a business, and contributed to ushering in the era of corporate ownership of casinos. He also had a long-term influence on other aspects of Las Vegas' growth and development.

Hughes was born in Dallas, Texas, on Christmas Eve 1905. His father, Howard Sr., was an oil prospector who was nearly broke, and his mother, Allene Gano, a prominent Dallas socialite. Hughes Sr.'s fortunes soared in 1909 when he perfected an oil drill bit that pierced bedrock, an invention that would also make Howard Jr. a wealthy young man as head of the Hughes Tool Company, in Houston, Texas.

Hughes grew up a rich man's son in the 1920s, going to private boarding schools and at one point receiving an allowance of $5,000 per week. While Howard Jr. was attending Rice University in 1924, his father died suddenly, leaving him most of the family tool business. Hughes, who was nineteen, got a judge to declare him an adult (which at the time typically came at age twenty-one), and he bought out the remaining shares in the company from relatives. In 1925 he married Houston debutante Ella Rice in an arranged marriage that some of his relatives had demanded in exchange for selling their shares to him.

Not interested in running the tool business, Hughes hired a thirty-six-year-old accountant, Noah Dietrich, who would remain with him for decades. Hughes moved to Los Angeles and started financing movies and enjoying nightclubbing in Hollywood with film actresses while neglecting his wife. He became notorious for spending large sums of money on clothing, expensive cars, and failed investments.

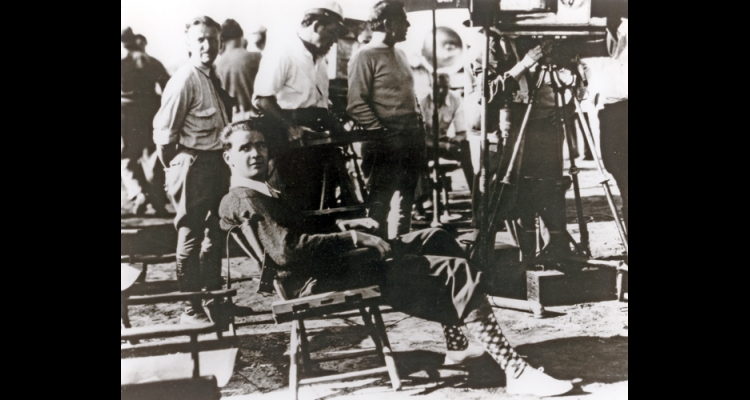

Hughes had learned to fly biplanes while a teen. In the late 1920s, he helped to direct—and fly a plane in—an aviation thriller film he produced, Hell's Angels. During a flight over the film set, he crash-landed his plane and a piece of metal remained lodged in his skull the rest of his life. He suffered from migraine headaches, and erratic and even bizarre behavior, until his death.

Hughes divorced Rice in 1929 and embarked on the first of many affairs with Hollywood starlets that over the decades included Katherine Hepburn, Bette Davis, and Ava Gardner. Thousands of people crowded the premiere of Hell's Angels in Hollywood in 1930, and Hughes was a movie mogul at the age of twenty-five. Showing bravado as a pilot, in California he flew a special plane he designed, the H-1 Silver Bullet, and broke the world flying speed record in 1935. Two years later, he set a new record in the H-1 by flying from the West to the East Coast in seven and a half hours. In 1938, radio listeners monitored him as Hughes flew a new plane, the Lodestar, across the world in under four days, setting yet another world record. A day after landing in New York, Hughes, a national hero, was greeted by a parade attended by more than a million people.

Hughes' tool company remained a financial success throughout the 1930s and into World War II. In 1939, he bought control of Trans World Airlines, a passenger airline. He transformed the passenger industry when he used his tool company to buy a fleet of forty new Lockheed airliners that could go from New York to Los Angeles in only ten hours.

In the mid-1940s, aides to Hughes began to see him exhibit obsessive-compulsive behavior, after injuries from the crash of an amphibian plane he flew over Lake Mead near Las Vegas in 1943. Another aviation catastrophe befell him in 1946, when his newest plane, the XF-11, developed engine trouble and crashed into a house in Beverly Hills, California. Badly burned with multiple fractures and his face disfigured, Hughes survived but began taking painkillers, which resulted in a life-long dependence on prescription drugs.

Hughes bought the film studio RKO in 1948. He also started dating actress Jean Peters whom he married privately in Tonopah, Nevada, in 1957. In the late 1950s, his TWA airline was losing out to its competitors, which were using jet aircraft. But his aviation company, Hughes Aircraft, brought him even more success, such as when it developed the lunar spacecraft that landed on the moon with Apollo 11 in 1969.

Hughes frequently exhibited compulsive behavior, using sheets of paper tissues on doorknobs and telephones to avoid contamination. By the late 1950s, he was diagnosed with neurosyphilis, a venereal disease affecting the brain. His symptoms included irritability, delusions, and carelessness about personal hygiene and grooming, which plagued his later years. His fear of contamination led to his insistence on living in a "germ-free zone." Hughes became reclusive in the early 1960s when he moved with Peters into a highly guarded mansion in the wealthy Bel Air section of Los Angeles.

The settlement of a lawsuit involving TWA resulted in Hughes receiving almost $500 million for his shares in the company. He claimed to be worth about $2 billion at the time and sought to avoid California state taxes on his TWA windfall. In 1966, Hughes asked his top aide, Robert Maheu, to find a way for him to sneak out past Peters so he could go to Las Vegas where the billionaire intended to become "the largest single property owner in the gambling capital."

Dressed in blue pajamas, Hughes arrived secretly on a private train in the pre-dawn hours of November 27, 1966. His aides took him by stretcher to a service elevator at the Desert Inn Hotel-Casino on the Strip and up to the ninth floor suite, which Maheu had reserved for him. Weeks later, when Desert Inn executive Moe Dalitz told him he had to leave, Hughes offered to buy the place. Dalitz quoted him an inflated price, $13.2 million, but Hughes accepted it and took over the Desert Inn on March 31, 1967.

That same year, Hughes continued what would be an unprecedented buying spree of Las Vegas Strip casinos. He spent $23 million for the Sands Hotel, $3.3 million for the Castaways and $23 million for the New Frontier. In 1968, he spent $5.4 million for the Silver Slipper and $17.3 million for the Landmark. His deal to buy the Stardust for $30.5 million would later fall through. Hughes also acquired the Harolds Club Casino in Reno for $10.5 million.

In some cases, Hughes' purchases of the Las Vegas casinos ended more than two decades of hidden ownership by organized crime members (such as Dalitz) in Strip casinos. His involvement changed the nation's perception about the gambling business in Las Vegas, and this new respectability encouraged public corporations to buy or invest in Nevada casinos as never before.

Hughes also benefited from special treatment. Governor Paul Laxalt, eager to remove the stigma of organized crime from Nevada gaming, encouraged Hughes' purchases. Because of the intervention of Laxalt and other state officials, Hughes became the only licensee who was never required to appear personally before the Nevada Gaming Control Board or the Nevada Gaming Commission, arguing that Hughes was a special case.

By the late 1960s, Hughes had spent $65 million on Las Vegas Strip hotels and local real estate, including a sprawling section of land in the northwestern section of the Las Vegas valley that became, starting in the 1980s, a housing development called Sun City Summerlin. Hughes was Nevada's largest single property owner at the time, with almost 2,000 hotel rooms and twenty percent of the rooms on the Strip under his control.

Hughes' now-legendary eccentric behavior extended to broadcasting when he bought the local television station, KLAS Channel 8. His sole purpose for acquiring the station was that he disliked its policy of going off the air late at night. Once he owned it, he is said to have insisted that it show movies all evening long so he could watch them.

To interest his wife, Jean, in moving to Las Vegas, Hughes bought property in Rancho Estates, a private exclusive neighborhood west of downtown. He also purchased the expansive Spring Mountain Ranch, about twenty miles west of Las Vegas, from wealthy heiress Vera Krupp. Peters refused to move, and the couple divorced in 1970.

While in Las Vegas, Hughes employed key aides who belonged to the Church of Latter Day Saints. Mormons were prohibited from doing two things he did not do—drink alcohol and smoke. Hughes was known to dine on TV dinners and fast-food sandwiches while watching movies in his darkened hotel suite at the Desert Inn. He was also addicted to painkillers. Some biographers allege that his aides, nicknamed the "Mormon Mafia," deliberately cut him off from the outside world and enabled his addiction to painkillers. For years, he communicated with his aide, Maheu, only by phone or written notes—one of Hughes' highest ranking employees never met his employer face-to-face. Hughes became so reclusive that Governor Laxalt insisted on talking to him by phone in 1968 to make sure he was really alive.

In 1970, Maheu got into a dispute with Hughes' Mormon aides, which led Hughes to fire Maheu. On Thanksgiving Day, 1970, four years to the day of his arrival, Hughes—who had never emerged from his hotel suite those four years—secretly left Las Vegas, with the help of his remaining assistants, in a stretcher. He moved to the Bahamas and left control of his Las Vegas empire to another aide, Bill Gay.

In 1972, while in the Bahamas, Hughes consented to a long interview, by phone, with news reporters to denounce a supposed biography of him as a forgery. He told them he was interested in moving back to Las Vegas to oversee his Strip hotels once again, but he never returned there. With no one but his aides around him, Hughes neglected his personal appearance and hygiene. He rarely bathed; his hair was down to his shoulders, his fingernails long and claw-like, and his body almost skeletal.

But in 1973, Hughes cleaned up and went off painkillers briefly so that he could take up flying again in London, England. He made four flights in a twin-engine propeller plane, including one over the English Channel to Belgium, and his spirits were high. However, after suffering a fall in his hotel room in London later that year, doctors put him back on painkillers, and his addiction resumed.

In 1976, Hughes, weighing only ninety-three pounds, was found unconscious from painkillers in his hotel room in Acapulco, Mexico. His aides chartered a jet plane to take him to a hospital in Houston, Texas, but he died during the flight, at age seventy.

Hughes was perhaps Las Vegas' first true casino mogul. His main legacy to Las Vegas is that, by buying six major Strip casinos in the late 1960s, he removed the perceived taint of organized crime on casino gambling in the national marketplace. His actions triggered a major trend, still evident today, whereby public companies bought, held interests in or granted loans to most of Nevada's largest casinos. That involvement vastly increased the investment capital available from Wall Street, and led to the multibillion-dollar expansion of the Las Vegas Strip that started in the late 1980s.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.

Further Reading

None at this time.