Katherine Lewers

Katherine Lewers studied at the New York School of Applied Design for Women and St. George's Art School in Glasgow, Scotland. She joined the University of Nevada faculty in Reno in 1905 and taught a variety of disciplines until her retirement in 1939. Regarded as an eccentric old maid by some, Lewers lived on a ranch in Washoe Valley south of Reno and commuted to classes on the Virginia and Truckee Railroad. Most of her paintings have been lost, lessening the opportunity for their examination and assessment.

Below is reprinted with permission from the Nevada Historical Society Quarterly.

Nevada Historical Society Quarterly

Volume 33, Summer 1990, Number 2

Margaret Ann Riley

KATHERINE LEWERS (1868-1945)

Kate Lewers is fondly remembered as an eccentric old maid who taught art at the University of Nevada early in this century. To dismiss Kate Lewers so lightly is to disregard an active artistic intellect at work. Lewers thoughtfully explored the tenets of the Scottish painter-etchers' movement; she discovered new methods for using artists' materials; and her teaching encouraged students to develop their own unique talents.

Kate Lewers was born in 1868 to a family noted for intelligence and independence. Her mother, Catherine Taggert Lewers, was well educated and knew the botanical names for all the plants, trees, and shrubs on their Washoe County ranch. She raised flowers for commercial sale, daily sending bunches of blossoms to market in Virginia City. Mrs. Lewers was one of the first in the Washoe area to collect weather information on a regular basis, sending it to Washington, D. C. Ross Lewers, her husband, raised cattle and farmed. He took particular pride in his apple orchards and cultivated a variety of special species.1

Kate Lewers attended the University of Nevada in Reno and then taught school. Her first teaching post was at the Mill Station District in Washoe Valley during 1891-92; she later taught grade school in Reno, in 1895-96, for which she received a monthly salary of $50.2

At the turn of the century Kate Lewers embarked on an extensive five-year program of formal art training: She was thirty-two years old. The encouragement and financial backing of her parents and older brothers made this undertaking possible, as her teaching salary alone could never have sustained such a course of action. The decade spanning the ages of thirty and forty is the time when never-married women and their families realize that these women have become anomalies. In her study of women who have never married, Barbara Levy Simon of Columbia University finds that a majority of these women remember that it was at this stage that their families offered extensive emotional support for their individualistic behavior and material aid for additional education or vocational training as well. With such family support Lewers began her training as an artist.3

An early opportunity came when Lewers won a scholarship from the New York School of Applied Design for Women in New York City. The school offered a two-year degree program that focused on drawing, design, and illustration for industry or manufacturing.4 Study followed in Washington, D. C., at the Corcoran, a non-degree school specializing in drawing instruction. Lewers's brother, Albert, lived in Washington, and may well have opened his home to her at this time or supplied financial support, as he did later.5

While in Washington Kate studied with Howard Helmick, a professor at Georgetown University. Helmick was a painter, etcher, and illustrator and was a member of the British Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers.6 As a member of the society, Helmick maintained a close and lively interest in the organization's yearly exhibits in London. At this time the society's major awards for etching were being swept up by Scottish artists David Young Cameron, Muirhead Bone, James McBey, and William Strang. British and American art publications reviewed these Royal Society exhibits, debating the merits of works and focusing on the award winners. David Young Cameron and Muirhead Bone were receiving particular attention, and the 1902 withdrawal from the society by Cameron and Strang was the subject of international publicity as well.7

E. S. Lumsden, writing in the 1920s, names Cameron, Bone, and Strang as the great men of the Scottish painter-etcher movement and defines the tenets of that movement: First, these painter-etchers revolted against the vision and principles of the French Impressionists and of James McNeill Whistler's later atmospheric paintings. Second, they emphasized a return to individual study of nature and to its realistic interpretation. Third, they revived the study of the Dutch masters, in particular Rembrandt. Although French Impressionism is today one of the most familiar and generally popular schools of art, this popularity has not always been universal: Turn-of-the-century Scottish artists were adamant and vocal in their rejection.8

As Kate Lewers was studying with Helmick during this period, it was inevitable that she became aware of the work of these Scottish artists. Glasgow was their major center, and both Cameron and Bone were residing, working, and exhibiting there. Kate Lewers enrolled in St. George's Art School in Glasgow.9 To choose to attend art school in Glasgow at this time, rather than a school in Paris or London, shows a dedicated interest in the particular principles and methods developed by these men.

In 1905 Lewers was hired by the University of Nevada to teach freehand drawing for $100 a month. By September she had been granted a letter of appointment to teach drawing and biology, at a yearly salary of $1,500.10 She lived at the family ranch in Washoe Valley, and commuted on the Virginia and Truckee Railroad each week, perhaps staying with her brother, Robert, who lived in Reno and taught at the university. She later drove her automobile into town from the ranch and often ended up stuck in the winter's snow or mud. She would wait, knowing someone would be sent to find her when she didn't show up to teach class.

In 1907 Lewers received an assistant professorship. She added elementary painting to the university's curriculum, and extended her drawing classes to include the regimented instruction in mechanical drawing necessary for engineers, teachers, and home-economics students.12 In 1912 she took a sabbatical leave with half pay to go to Paris, although nothing is known of this visit.13 Kate Lewers was made a full professor of art in 1914, with a salary raise to $1,800 a year. Lewers believed that students develop their talents naturally, and she gave them wide latitude to do their own work and form their own individual styles. She accepted both great and limited talents in her classes, never praising the one over the other, or lavishing attention on a favored few.14

Her students were supplied with basic technical information, but the emphasis was on the individual student expanding and developing these techniques. She showed only how to mix colors from the primary palette of yellow, blue, and red. One student recalls asking how to mix a particular shade of blue and having Lewers respond, "That's for you to figure out." Lewers stressed looking closely at the subject being painted. She would give pointers on sun and shadow, shape and line, but directed the students to look—"If you don't look at something you will never see what to paint"—and then to paint as they saw. Her training in Scotland had emphasized the importance of looking and painting what was seen rather than what was felt or gathered from the scene.15

Lewers became an ardent photographer and used photographs in developing her paintings as well as to record events. One of her photographs records a formal composition of daisies and greenery, a study for a future painting. Another, published in the 1920s, shows two of her students painting an outdoor scene on the university campus. There is also a photograph of the mechanical drawing class that may well be Lewers's work.16

Lewers was always a quiet and even-tempered teacher, but when her father died in 1918 she became withdrawn and was said to have become a hermit. Yet, art-student visitors were always welcome at the Washoe Valley ranch, and there were still summer lessons for those who wanted them. She was well liked although not a warm or humorous woman. Numerous stories are remembered and told of her—"a total character." She was petite, wiry, always in a hat with veil and old-fashioned dress, walking briskly. Later students remember that her legs and feet became badly swollen, so she always wore rubbers for shoes. The ducks and chickens at the ranch were her friends, each with its proper name. She hired local children to help maintain the extensive flower garden her mother had developed, to mow lawns, and to pick apples, refusing to use any kind of mechanical picking devices. She made and sold hard cider to the university students in her classes.17

A March 1921 item in the Reno Journal reports on an article in Scientific American in which Lewers is credited with perfecting a method for blending crayons: kerosene applied to the back of heavy paper allowed crayons to be blended and shaded much in the manner of today's oil pastels. Lewers also advocated the preparatory use of kerosene on paper in order to cut the gloss of oil paints: There was no gloss in nature, and therefore paintings from nature should have none.18

Lewers retired in 1939 after serving on the University of Nevada faculty for thirty-four years. She refused to accept her university pension, living on the lease payments for portions of the Washoe Valley ranch and additional sums sent by her brother Albert. She actively managed the ranch, gave private art lessons and carried out "certain experiments in art" until her death in 1945.19

By 1970 Kate Lewers's art was judged passé by biographers Myra Sauer Ratay and Doris Cerveri. In the era of abstract and emotion-filled action painting, direct representation of nature would most certainly have seemed out of style. Reassessment of her work has now become conjectural because a portion of her oeuvre disappeared during the 1980s. There had been drawings, photographs, and paintings of the University of Nevada campus, scenes along the Truckee River, and the area around the family ranch in Washoe Valley. But today only eight authenticated paintings are available for study.20

Kate Lewers painted in the formal tradition of the Dutch masters of the seventeenth century. Her still lifes of flowers from her mother's garden seem to conform to most of the conventions of this genre. Floral Arrangement with Hollyhocks is a mixed bouquet of flowers. A configuration of blossoms and greens, designed to all but hide the vase, is placed against a deep-plumcolored background. Roses in a Round Vase shows pink and cream roses in a glass or shiny metal container. Following the Dutch painters, Lewers painted the reflection of the room shown in the bulging side of the vase. Pink Roses focuses on four pink roses. Lewers favors the full blown—to our eyes, past-their-prime roses that appear in Dutch painting. Red Tulips is another study that concentrates on the stages of blossom maturity.21

Working in the manner of Dutch still-life painters of the seventeenth century was in accord with Lewers's training with the Scottish artists: realistic rather than impressionistic painting, personal interpretation of nature, and study of the Dutch masters. Lewers worked within these bounds, but not without thought and consideration of alternative methods. An unfinished piece shows use of white or cream ground rather than the "brown gravy" ground favored by Rembrandt and other Dutch painters.22

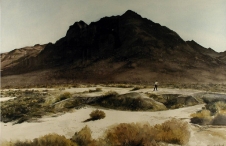

Lewers's other paintings, Orchard, Duck Pond and Poppies under the Walnut Tree, are intimate views of specific places on the ranch. Here again, her care for accurate detail in the rendering of flowers, plants, and trees shows the influence of her Scottish mentors.

Much has been made of Kate Lewers's eccentricities: her never-married state, her quiet manner, her pet ducks and chickens, her out-of-date manner of dress, her old-fashioned painting. Lewers chose to explore the principles of the Scottish painter-etchers' movement, once vital, but today obscure and forgotten. To characterize her as simply odd ignores the independence, intelligence, and talent of this artist.

NOTES:

* The author would like to thank Henry Heidenreich. Jr., long-time family friend, who answered questions, shared memories and family photographs, and granted considerable time for studying and photographing Lewers's paintings. Others who shared memories were Eslie Cann, Margaret Erwin, Robert Geyer, and Mara Wilson. Research assistance came from Lee Mortenson and Caroline Morel, Nevada Historical Society Library; Eslie Cann, Nevada Historical Society Photograph Collection; Cheryl Fox, Assistant Director, Nevada Historical Society; Karen Gash, University of Nevada, Reno Archives; and Barbara Buff, Museum of the City of New York.

1. Myra Sauer Ratay, Pioneers of the Ponderosa (Sparks: Western Printing & Publishing Co., 1973); Henry Heidenreich, Jr. interview with author, Heidenreich Ranch, Washoe Valley, Nevada, 27 November 1989; "Kate Lewers did 'her thing' before it became fashionable," Apple Tree, 16 January 1977.

2. "Kate Lewers did 'her thing' before it became fashionable," Apple Tree, 16 January 1977; Nevada Historical Society Nevada Teachers File 1864-1926, Reno, Nevada; State of Nevada, Biennial Report of the Superintendent of Public Instruction 1895-96 (Carson City: State Printing Office, 1897).

3. "Arts and Artists," Reno Evening Gazette, 22 March 1941; Barbara Levy Simon, Never Married Women (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1987).

4. Nevada State Journal, October, 1945; Florence N. Levy, American Art Annual 1898 (London: Macmillan & Co., Ltd., 1899).

5. Nevada State Journal, October, 1945; Myra Sauer Ratay, Pioneers of the Ponderosa (Sparks: Western Printing & Publishing Co., 1973).

6. Lillian Borghi "Arts and Artists," Reno Evening Gazette, 22 March 1941; Peter H. Falk, Who Was Who in American Art (Madison, Conn.: Sound View Press, 1985).

7. Joan Ludman and Lauris Mason, eds., Print Collector's Quarterly: An Anthology of Essays on Eminent Printmakers of the World (New York: KTO Press, 1977); Frank Hinder, D. V. Cameron: An Illustrated Catalogue of His Etchings and Dry-points, 1887-1932 (Glasgow: Jackson, Wylie & Company, 1932).

8. E.S. Lumsden, The Art of Etching (London: Seeley Service and Company Ltd., 1924).

9. Joan Ludman and Lauris Mason, eds., Print Collector's Quarterly: An Anthology of Essays on Eminent Printmaker's of the World (New York: KTO Press, 1977); Frank Rinder, D. Y. Cameron: An Illustrated Catalogue of His Etchings and Dry-points, 1887-1932 (Glasgow: Jackson, Wylie & Company, 1932); Nevada State Journal, October, 1945.

10. "Minutes of the University of Nevada Board of Regents" (Reno: University Archives, handwritten copied on microfilm).

11. Henry Heidenreich, Jr., interview with author, Heidenreich Ranch, Washoe Valley, Nevada, 27 November 1989; "Kate Lewers did 'her thing' before it became fashionable," Apple Tree, 16 January 1977.

12. "Minutes of the University of Nevada Board of Regents" (Reno: University Archives, handwritten copied on microfilm); James Warren Hulse, The University of Nevada: A Centennial History (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1974).

13."Minutes of the University of Nevada Board of Regents" (Reno: University Archives, handwritten copied on microfilm).

14. "Minutes of the University of Nevada Board of Regents" (Reno: University Archives, handwritten copied on microfilm); "Kate Lewers did 'her thing' before it became fashionable," Apple Tree, 16 January 1977; Margaret Erwin, telephone interview with author, Reno, Nevada, December 1989.

15. Margaret Erwin, telephone interview with author, Reno, Nevada, December 1989; Robert Geyer, telephone interview with author, Reno, Nevada, December 1989; "Kate Lewers did 'her thing' before it became fashionable," Apple Tree, 16 January 1977.

16. Henry Heidenreich, Jr., interview with author, Heidenreich Ranch, Washoe Valley, Nevada, 25 January 1990; Samuel Bradford Doten, An Illustrated History of the University of Nevada (Reno: University of Nevada, 1924); Nevada Historical Society Photography Collection, Reno, Nevada.

17. Margaret Erwin, telephone interview with author, Reno, Nevada, December 1989; "Kate Lewers did 'her thing' before it became fashionable," Apple Tree, 16 January 1977; Mara Wilson, telephone interview with author, Reno, Nevada, December 1989; Eslie Cann, interview with author, Reno, Nevada, November 1989; Robert Geyer, telephone interview with author, Reno, Nevada, December 1989; Henry Heidenreich, Jr., interview with author, Heidenreich Ranch, Washoe Valley, Nevada, 27 November 1989.

18. Reno Journal, 23 March 1921, 8; "Kate Lewers did 'her thing' before it became fashionable," Apple Tree, 16 January 1977.

19. "Minutes of the University of Nevada Board of Regents" (Reno: University Archives, handwritten copied on microfilm); Henry Heidenreich, Jr., interview with author, Heidenreich Ranch, Washoe Valley, Nevada, 27 November 1989; Lillian Borghi "Arts and Artists," Reno Evening Gazette, 22 March 1941.

20. Myra Sauer Ratay, Pioneers of the Ponderosa (Sparks: Western Printing & Publishing Co., 1973); Henry Heidenreich, Jr., interview with author, Heidenreich Ranch. Washoe Valley, Nevada, 27 November 1989; Nevada Historical Society Papers 1913-1916. (Carson City: State Printing Office, 1917).

21. Lewers did not title her paintings. I have provided these titles to ease discussion of her works. Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin, Women Artists 1550-1950 (New York: Alfred A. Knoph, 1979).

22. Waldemar Januszczak, Techniques of the World's Great Painters (New Jersey: Chartwell Books Inc., 1980); Bernard Chaet, An Artist's Notebook. (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1979). The ground of a painting is its initial coat of paint. Dark grounds darken colors applied later, light grounds brighten them.

Article Locations

Related Articles

Further Reading

None at this time.