Literature of Nuclear Nevada

The story of nuclear Nevada can be divided into two categories, reflecting the reality that Nevada has endured two nuclear ages. Artistic responses to these events constitute the literature of nuclear Nevada.

The first category might be labeled the literature of the Nevada nuclear testing era, which commenced at the Nevada Test Site (NTS) at dawn on January 27, 1951, with the atmospheric detonation of a one-kiloton weapon named Able. It ended on September 23, 1992, with the detonation of an underground nuclear test named Divider. Including Able and Divider, 930 nuclear devices were tested in Nevada, in the atmosphere and underground.

The second category might be labeled the literature of the Nevada nuclear waste era, which commenced in 1987 with the selection of Yucca Mountain (to the west of NTS) as the only site to be studied for potential use as the nation's High Level Nuclear Waste Repository. Yucca Mountain was formally nominated by President Bush in 2002 but has yet to be licensed for waste disposal.

These writers almost always approached the atomic era with feelings ranging from unease to dread, and often, indignation. There were no odes of praise, no depictions of mighty beauty. Instead, writers gave us anger over roasted test animals, fear in the image of a radioactive glow, and outrage over the diseases caused to people living downwind from the above-ground tests. And when Nevada seemed destined to host the nuclear waste repository, writers fretted over the long-term danger of the project and expressed anger over Nevada's treatment as the nation's garbage dump.

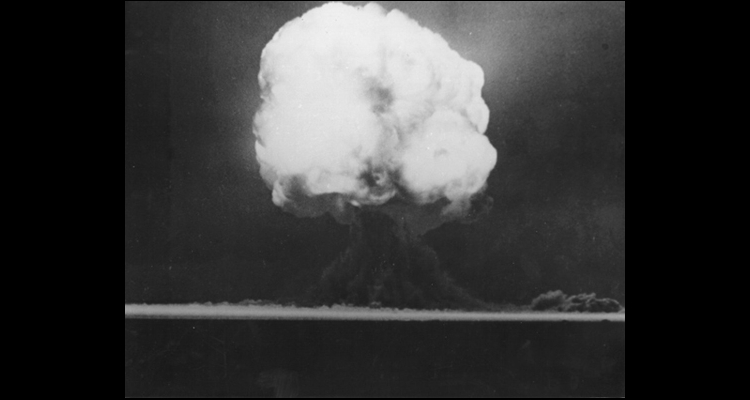

Many of the testing-era works of literature were produced by writers who experienced in some personal way the landscape of the desert site or the signature moments of an atomic test: the Teller light, followed by blinding flare, surreal atmospheric light show, thundering concussion, ascending mushroom cloud, and swirling winds which blew the cloud (usually) toward Utah. Poets rendered such personal experience as elegy or lamentation. Denise Levertov, after watching a documentary film featuring footage of test site animal experiments, wrote, "men are willing to call the roasting of live pigs a simulation. The pigs are real, their agony real agony." ("Watching Dark Circle," 1995). William Stafford wrote, "At the Bomb Testing Site / At noon in the desert a panting lizard / waited for history" (Stories That Could Be True: New and Collected Poems, 1977). Chicano poet Robert Vasquez, in "Early Morning Test Light Over Nevada," used his father's voice to describe a test which took place while Vasquez was yet in his mother's womb: "When the sky flared, / our room lit up. Cobwebs / sparkled on the walls, and a spider / absorbed the light." Native American poet Adrian Louis laments that "Taibohad to drop hydrogen bombs / where / thousands / of years / of our blood / spirits lie" ("Nevada Red Blues").

As data on fallout from the Nevada tests became more readily available, the literary focus shifted from descriptions of atomic bomb tests to explorations of cultural and health-related themes, including the fate of downwinders. Corrine Clegg Hales, in a poem titled "Covenant: Atomic Energy Commission, 1950's" (2002), introduces the irony that "We've been expecting / Such unambiguous Russian-made tragedy" that we missed the atom bomb "sneaking in through the side door, blowing / Like a tumble weed across the desert." Hales contrasts images of Atomic Energy Commission monitors chasing pink (radioactive) clouds with images of small children playing in Utah fields: "Eating apples, riding horses, scratching their names / In the fine dust coating every flat surface." Poet Lynn Emanuel invents an alter ego/narrator to examine bomb-light and bomb-legacy from the viewpoint of a girl living in Ely, Nevada, 250 miles north of the test site: "Bathed in the light of KDWN, Las Vegas, my crouched mother looked radioactive, swampy, glaucous, like something from the Planet Krypton." ("The Planet Krypton" in Atomic Ghost: Poets Respond to the Nuclear Age, 1995).

Among the best nonfiction works to examine the plight of downwinders is Terry Tempest Williams' "The Clan of the One-Breasted Women," a chapter in Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place (2000). Williams makes the connection between her memory of seeing the flash from one of the bomb tests and the death of her mother, grandmothers and six aunts from breast cancer. Dayton Duncan, like Williams, examines the devastation and death left in the wake of a singular atomic test, in this case, Harry, now known as Dirty Harry, in Miles From Nowhere: Tales From America's Contemporary Frontier (1993). Rebecca Solnit's Savage Dreams (1994) lyrically examines the test site landscape, peace activism at the site, and stories told by Native Americans and downwinders. Carole Gallagher's American Ground Zero offers photographs and narratives from test site workers, soldiers, and downwinders, placing faces on stories of leukemia, breast cancer, stillbirths, and government deception.

Notable among works of testing-era fiction is Frank Waters' The Woman At Otowi Crossing (1966). The narrator, Turner, describes Las Vegans preparing for an atmospheric test and provides glimpses of Camp Desert Rock as soldiers prepare to march into ground zero. In several remarkable passages, Turner ruminates on the fate of Mr. Mannequin and his Mannequin family—dummies positioned in Doom Town on the test site to soundlessly await obliteration by an atomic blast.

Another work of fiction is Downwinders: An Atomic Tale (2001), a collaborative work by Utahans Curtis Oberhansly and Dianne Nelson Oberhansly. It features Porkchop, a marine marched into ground zero during a fictional test named Huey. Atomic Express (1997) by Richard Miller incorporates elements of allegory. In a race against a ticking armed bomb, Miller places characters representative of different political approaches to nuclear testing (military advocates, peace activists, disillusioned scientists). The novel is textured with fascinating technical details about bomb testing.

The second category, the literature of Nevada's nuclear waste era, includes novels by Frank Bergon and James Conrad, essays by Richard Rawles, Corbin Harney, and William Kittredge, and poetry by Shaun Griffin. Nevada-born Bergon sets his witty and intelligent novel, The Temptations of St. Ed and Brother S (1993), in a Cistercian monastery adjacent to a site that has been selected by the Department of Energy (DOE) to serve as a nuclear waste dump. Conrad's novel, Making Love to the Minor Poets of Chicago (2000), follows the adventures of a fictional female Chicago poet/narrator who signs up as a tour guide for Yucca Mountain excursions so as to clandestinely research a commissioned epic poem about nuclear waste.

Rawles' essay "Coyote Learns to Glow" applies the "coyote principle" to Yucca Mountain. The "principle" is taken from a scene in a Louis L'Amour western in which a coyote loosens a rock and exposes a mother lode of gold. What if, ages hence, the lethal Yucca Mountain mother lode is inadvertently exposed? Essayist and Native American Corbin Harney (The Way It Is, 1995), believes that even without burying wastes, the day will come when the nuclear whirlwind is reaped: "The vision showed me that this place [where deep holes were drilled to emplace atomic weapons] is now beginning to fill up with water. The water is filling up those holes." On Nevada's nuclear waste dilemma, Harney writes, "Yucca Mountain lies asleep like a snake."

Kittredge, a powerful and respected Western voice, expresses his philosophical distrust of the "quiet empire" of military and DOE and argues passionately for loving a Nevada "our nation seems to think of as a vast, convenient dumpster out there waiting to be filled." ("In My Backyard"). Like Kittredge, poet Shaun Griffin speaks to geopolitical and environmental injustice. His poem, "Nevada No Longer," begins and ends with the plaintive passage, "Nevada is never on the map, not now / not ever."

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.