Lubertha Johnson

Las Vegas community activist Lubertha Johnson was born in 1906 on a Mississippi farm, and raised by her grandmother. She had originally planned to be a teacher, but due to the Great Depression and her father's ill health, she was instead forced to join her family in Chicago to help support them.

In 1943, Lubertha accompanied her family to Las Vegas and became recreational director at the federally funded Carver Park housing project, which provided shelter for the Black workers at Basic Magnesium Incorporated (BMI), the plant that processed magnesium for aircraft and bombs during World War II. She also began to take an active interest in African American life in Southern Nevada, based on her family's belief that accomplishment came from education—and she accomplished a lot in Las Vegas.

Carver Park reminded Johnson of life in Mississippi; where Blacks and whites were kept completely separate. Starting the Tenants Council at Carver Park was Johnson's first major accomplishment. The Council organized discussion sessions around various topics, especially racial discrimination at the plant. These discussions led to Black men organizing and staging a strike in October 1943. Johnson's primary duties there allowed her to lead the recreation agenda, start a nursery school, and later add a preschool.

Johnson left Carver Park and became familiar with the Westside community, becoming active in the NAACP. She married in 1945 and she and her husband began looking to buy property, but they were only allowed to purchase land in the Westside community. One day while riding around, she found property out of town in an area called Paradise Valley. The seller was willing to sell the twenty-five acres to her, and so Johnson became a rancher without any experience.

However, the family's agricultural venture eventually failed, and they instead built a duplex and several single apartments as rentals, along with a barbecue stand. Groups used the property for meetings and picnics.

Next, Johnson enrolled in nurse training courses and worked for seventeen years at Southern Nevada Hospital, gradually giving up all attachments to the ranch and moving into the city.

After moving to the Westside, she continued to draw on the entrepreneurial spirit of her parents in order to do something about the deplorable housing situation in the Black community. The City of Las Vegas engaged her to conduct a housing survey that resulted in the federally funded Marble Manor Development, which opened in 1952. Not all of her desires for city improvement received such a rapid response, but Johnson and her associates continued to work hard and protest vehemently in the area of civil rights for African Americans in Las Vegas.

Prior to 1960, access to entertainment and amusement was restricted. Public swimming pools, restaurants, hotels, and gambling establishments did not allow Blacks to use the facilities. Movie theaters limited the areas where Blacks could sit to either the back or a certain side of the auditorium. Because Johnson did not experience the fear of speaking out against inequality as she did in Mississippi, she and her friends would stage their own protests. They made it a practice to sit in the center and would remain there until the police arrived. Consequently, they were thrown out of many places.

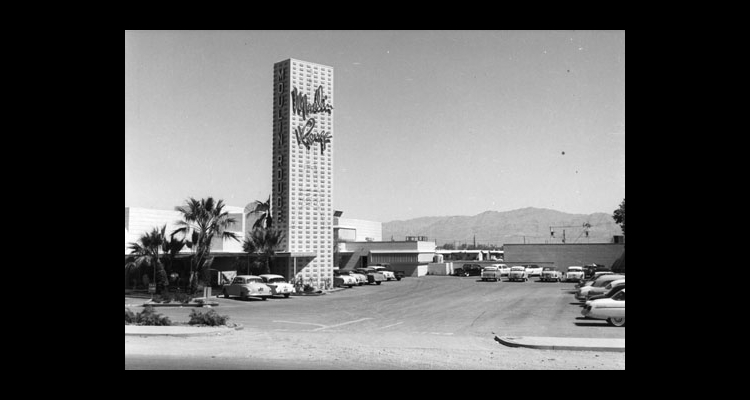

But the Strip was different. When Johnson and her friend Mabel Hoggard called for a reservation, their seats were assigned. Problems began when they arrived. They recalled that they never left, and were always seated in the establishments' efforts to prevent embarrassment. The act of protest that Johnson remembered best was when Josephine Baker performed at the El Rancho Hotel in the early 1950s under a contract that allowed an integrated audience. On the second night of her performance, the hotel stated that since they had adhered to the contract once, they would not have to allow Blacks in on the second evening of her engagement. The fifteen or twenty Black audience members, including Johnson, walked into the showroom with Baker but were refused service. So, Baker refused to perform; instead, she just sat on stage and did nothing. Once her Black guests were served, she put on her show.

Johnson's greatest work materialized under a multi-faceted poverty program. She ran the portion of the program that sponsored the Head Start Initiative. She named it Operation Independence and it soon became a private, self-regulating entity with its own board of directors. She served as director for twenty-one years, retiring at the age of eighty-one, three years before she died in 1990.

Lubertha Johnson was a wise community activist who enjoyed many victories, though she never thought of herself as a leader. She felt that her most significant contribution was the role she played in securing legal protection from discrimination. She even spoke before the state legislature during the struggle for civil rights. At the end of her life, she still believed in the potential that Las Vegas held for Blacks. "Here, there is really an opportunity to build and do new things and to develop in a way that we couldn't develop in many other cities."