National Mining Act of 1872

The 1872 National Mining Act emerged from decades of debate about mining and public lands. The British Crown, followed by American state and federal governments, experimented with the management of mineral resources. Their approaches ranged from reserving mineral wealth for the government to the leasing or sale of land.

The 1849 Gold Rush to California inspired tens of thousands to mine public lands throughout the American West largely without legal authority. This prompted a Congressional discussion about the appropriateness of charging miners who extracted minerals from federal property. Many believed people should pay for wealth gained from lands held in public trust. In 1849, Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton advocated expansion, not revenue, as the goal of federal policy for the West, with mining encouraged at no charge. The concept was analogous to the idea that land ought to be free for farming, codified by the National Homestead Act of 1862. Failure to reach consensus on mining inhibited Congressional action during the 1850s and early 1860s.

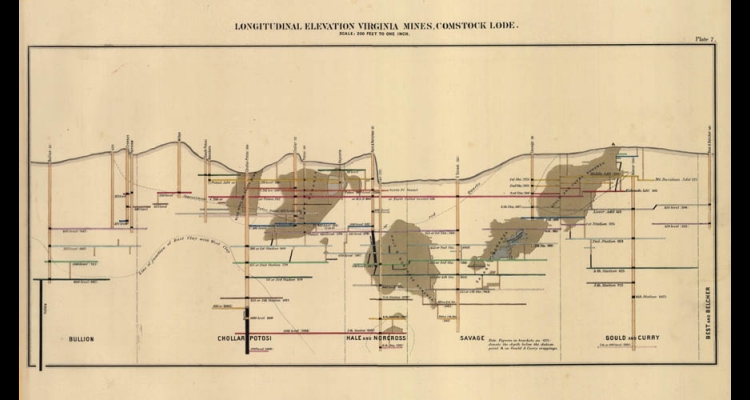

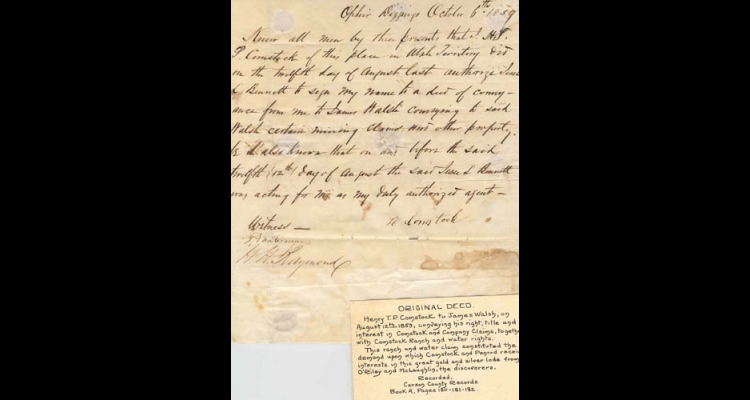

Debate on this question heated up early in 1865 just as Nevada Senator William Stewart began his first term. Stewart gained a seat on the newly-formed Senate Committee on Mines and Mining. He had earned a fortune as an attorney arguing the Comstock's Chollar-Potosi lawsuit and earlier had played an important role developing local mining regulations in California. His position and experience gave him power to influence future mining legislation. Stewart endorsed the concept of "free mining" to promote development.

At the same time, Congressman George Julian of Indiana introduced a bill to subdivide and sell mining land. Julian believed companies that invested in a region would be more likely to remain, thus promoting stability on the mining frontier as they produced a revenue stream for the federal government.

Debate focused on the Julian bill in the lower house, and the Stewart-supported approach in the Senate, but 1865 did not see a resolution. In 1866, Stewart drafted the National Mining Act. Julian opposed it, initially thwarting the bill's progress, but Nevada's senator led the "free mining" forces as they maneuvered past obstacles, adding their bill to another piece of legislation, before delivering it to President Johnson for his signature. For the first time since mining began on public lands, miners worked within a legal framework.

An 1870 amendment to the National Mining Law addressed placer miners, giving them an opportunity to purchase land they worked. Senator Aaron Sargent of California drafted a major amendment to the law in 1872, and again Stewart directed its progress through Congress. The new amendment attempted to correct several vague points in the 1866 law. The act required those drafting local mining codes to follow federal standards. It also clarified the documentation needed for a claim to be legitimate and defined the work required annually to maintain a claim.

The 1872 amendment included a flaw by asserting that the prospector who claimed the highest point of an ore body had the right to follow it underground. This inspired a great deal of legal action as contesting interests fought over which claim included this critical part of the deposit. Critics also maintained the 1872 amendment failed to overturn the 1866 assertion that local mining practice was a form of common law. Stewart believed, however, that mining district regulations adopted before 1866 should remain in force because overturning them would create chaos throughout the West.

Congress addressed the conflict between advocates of free mining and those who wished to charge for access to publicly held minerals, but the debate continued. In the early twentieth century, federal action removed energy-producing materials including coal, oil, gas, and phosphate from the jurisdiction of the 1872 mining law. National security and the potential for extravagant profits inspired the government either to conserve those materials or to charge for their extraction. Congress, however, left most precious metals, including gold, silver, copper, lead, and zinc, under the jurisdiction of the 1872 National Mining Law.

In the late twentieth century, environmentalists and others began to focus on what they saw as flaws in a century-old law. Many now maintain that mining companies could reap huge financial rewards by extracting a range of materials from public land. Examples of foreign corporate ownership exacerbate the perception that private interests inappropriately take the nation's property. Critics point out that the coal, oil and gas industries pay a 12.5% royalty on commodities taken from public land. They speculate that a similar fee on other minerals could generate approximately $400 million annually.

The mining industry has been quick to argue that operations rarely have outstanding profits and that the nation's commerce depends on affordable materials. In addition, mining supports small towns throughout the West, which would suffer financial hardship if federal fees forced mining companies to dissolve. Revenue would not reach projected levels because marginal operations would close, shifting work to foreign sites.

Environmentalists also pointed out that the National Mining Law did not address the environment or land reclamation. Subsequent federal legislation has had limited application to the mining industry, but the 1872 law represents an obstacle to those wishing more attention to reclamation and the protection of groundwater, for example. Many abandoned mines are a dangerous legacy, finding a place on the Superfund National Priorities List. The mining industry maintains, however, that national laws such as the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and state laws governing reclamation and groundwater require modern mining to meet strict environmental standards.

With Democratic control in Congress and the White House in 1993, reform of the National Mining Law seemed inevitable, but once again, consensus on this problematic subject remained elusive. Since 1995, the political balance has prevented amendments to the law.

Ironically, one of the popular misconceptions about Nevada is that statehood in 1864 was necessary so President Lincoln and the Union could profit from the Comstock's mines. In fact, the federal government had no means to benefit directly from the mines whether they were territorial or within a state.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.