Protest, Dissent, and Witness at the Nevada Test Site

Since the late 1950s, the Nevada Test Site has been the subject of criticism, protest, and civil disobedience. Organized protest actions have ranged in size from fewer than ten people to groups of thousands during the large demonstrations of the 1980s. Individuals have observed private desert witness as they pray for world peace. In spite of the nuclear testing moratorium that has been in place since 1992, protest continues at the site. In recent years, three major annual events have been observed: Holy Week, Mother’s Day weekend, and the August 6–9 anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II.

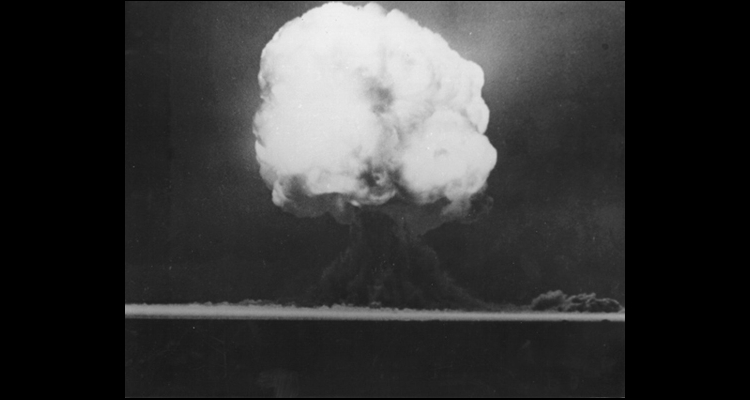

It is easy to characterize these demonstrations as being specific to the Nevada Test Site (NTS). However, since the dawn of the nuclear age, dissent has taken place within the larger context of national and global debates about the danger, necessity, and morality of nuclear weapons. Nuclear fission was discovered in 1938–39. By 1942, the achievement of the first manmade nuclear chain reaction meant that powerful explosions releasing the vast energies stored in the atomic nucleus were possible. The World War II Allies’ top secret Manhattan Project made that possibility a reality with the atomic bombs tested in New Mexico and used on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. During the war, scientists and statesmen who knew of these world-changing developments were deeply troubled and sometimes divided about whether research should focus on a weapon of such unprecedented destructive power. The decision to create and use the atomic bomb during World War II remains a subject of public and historical controversy.

Post-World War II, debate continued among American scientists and statesmen regarding international control of nuclear energy and nuclear weapons. However, failing to reach arms control agreements with the Soviet Union meant that the nuclear arms race would accelerate. In the 1950s, as thermonuclear weapons or “super” hydrogen bombs were invented and tested, concern grew that the world could become involved in all-out nuclear war with weapons of unlimited power and the potential to destroy civilization.

For the first protesters at the Nevada Test Site, memories of the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were still fresh. In 1957, a group of Quakers, Mennonites, and other pacifists traveled from out-of-state to commemorate the twelfth anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on August 6. Their protest coincided with the detonation of the Stokes device at the NTS on August 7. Stokes—the test of a multi-purpose warhead—was detonated from a balloon over Yucca Flat. It was one of twenty-nine tests in the Plumbbob series carried out between May 28 and October 7, 1957. The Hood test of July 5, 1957, had yielded seventy-four kilotons—the largest of all atmospheric tests at the NTS. Stokes, at nineteen kilotons, approximated the yields of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs. Protesters set up camp close to the test site boundary and held a prayer vigil during the actual test. Those who crossed into the test site at the guard station were arrested.

Another important landmark in the history of test site dissent was the eight hundredth anniversary of the birth of St. Francis of Assisi in 1982. At that time, members of the Franciscan religious order in Las Vegas decided to hold peace vigils and desert witness at the NTS to honor their patron. These activities followed the precepts of nonviolent civil disobedience.

Over time, protests grew to encompass the interests of a wide range of individuals and organizations, some of which advocated more confrontational approaches, including resisting arrest. A peace camp was established across the highway from the test site where people still hold vigils, ceremonies, and religious services. From there, those who wish to “cross the line” can walk under the highway and step over the test site boundary, after which they are arrested. Individuals and small groups have also entered the test site from remote desert locations and have been able to evade security for many hours before being detected. In at least one case, their presence on the test site delayed the scheduled detonation of an underground test. Over the years, those arrested have been held in fenced areas at the test site, sent by bus to Tonopah and Beatty, Nevada, jailed, or sometimes handcuffed, ticketed, and released.

In addition to faith-based, pacifist desert witness, others journey to the NTS to express deeply held convictions about nuclear weapons. Hibakusha—survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—are important participants in international peace and anti-nuclear movements. “Downwinders” from Nevada, Utah, and Idaho come to bring attention to the illnesses they believe were caused by fallout from more than a decade of atmospheric testing at the NTS. Many downwinders consider themselves to be hibakusha, atomic bomb victims along with the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Pacific Islanders in whose traditional territories the Pacific nuclear tests were conducted. Atomic veterans—military personnel who were exposed to radiation during tests at the NTS and Pacific—also participate in protests. However, some atomic veterans consider it unpatriotic to demonstrate, seeing their illnesses as combat injuries of their military service. Environmental activists and citizens concerned about the safety of soil and ground water organize and attend rallies. During the cold war, elected officials demonstrated in support of policy changes such as a nuclear freeze and U.S. ratification of international test ban treaties.

The test site is located on the traditional lands of indigenous peoples, including the Western Shoshone and Southern Paiute. Ancestral and cultural resources are located within its boundaries. Some reservations as well as traditional hunting grounds were in the path of test site fallout. The Western Shoshone claim the test site as part of their homeland, Newe Sogobia, under the 1863 Treaty of Ruby Valley. During protests, tribal leaders issue passports granting permission to enter the test site. The Nevada-Semipalatinsk Movement brought together activists from the United States and Kazakhstan, location of the major Soviet test site. During the early 1990s, Kazakh and Native American leaders joined in ceremonies at the NTS.

During Holy Week, some groups walk from Las Vegas to the Peace Camp as part of their religious observances. They enact the “nuclear stations of the cross” and Catholic mass is held in the desert. During Mother’s Day weekend, tribal leaders run for miles across their traditional homelands to gather for ceremonies near the test site in honor of Mother Earth. During the August Desert Witness, Las Vegas faith-based organizations hold teach-ins on nonviolent action and rally with others at the test site to remember Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Over the years, test site administrators and security personnel, including the Nye County sheriff, have dealt with the demonstrations in a variety of ways. Some protesters and security people have become close friends, having gotten to know each other over decades of protest. For some test site workers, the protests represent a personal attack on their morality. Many believe that their cold war work assured nuclear deterrence and contained the Soviet threat to American values, including the right to protest. These arguments in Nevada embody the complex moral dilemmas that nuclear weapons have raised since they were first discovered.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.