Reno and the African American Divorce Trade: Two Case Studies

From 1906 until the late 1960s, Reno, Nevada was known as the "Divorce Capital of the World." Before the modern age of no-fault divorce, legal dissolution of marriage could take years, or it was simply not allowed. Early in the twentieth century, a number of states competed for the nation's migratory divorce trade and the economic opportunities found in offering relatively quick divorces. Lenient divorce laws were usually centered on a residency requirement and allowable grounds for divorce. In 1931, when the Great Depression was raging, Nevada cornered the migratory divorce market by lowering its residency period to six weeks.

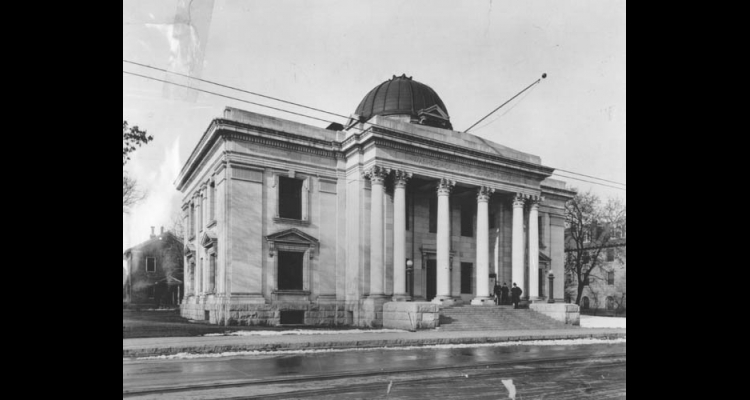

Reno was the state's largest city at the time and the center of the divorce trade. The town developed a well-oiled machine that included a wide selection of divorce lawyers. Hotels, boardinghouses, and divorce ranches provided necessary housing, ensuring that the six-week residency requirement was given sufficient authority to assuage the charges that it was a legal sham. During the 1930s, the Washoe County Courthouse processed more than 30,000 divorce cases, mostly for people from other states and countries.

While The Biggest Little City in the World welcomed divorce seekers from all socioeconomic levels and diverse ethnic origins, it was not progressive in its dealings with racial minorities, a reality that extended to the divorce trade. Although not formally legislated, the city openly practiced strict racial segregation from the early 1900s through the 1960s. Most minorities were restricted in their housing and employment options, and they were not served in white restaurants and bars. African Americans could not enter white casinos or seek accommodations in white hotels.

In his book, Special Delivery: the Letters of C.L.R. James to Constance Webb, 1939-1948, journalist C.L.R. James described his experiences in segregated Reno. Cyril Lionel Robert James was a noted Black Marxist scholar who came to Reno from New York to divorce his first wife so his marriage to white actress and socialist Constance Webb would not expose him to charges of bigamy. James had previously obtained a Mexican mail-order divorce that was not recognized in the United States. He was also evading immigration officials because he had let his British passport expire.

James arrived in Reno on August 2, 1948. When he asked for a lodging recommendation, a white taxi driver took him to a boardinghouse at 539 Sierra Street that the driver called "a Black person's place." Eating out had its limitations, as well. James found two integrated establishments—a Chinese restaurant and a "Negro place." Otherwise, he observed, "the Jim Crow here in restaurants is powerful." Reno's small Black community quickly accepted him and he was struck by their solidarity. Unsuccessful in his attempts to find a qualified African American lawyer to handle his case, James engaged Charlotte Hunter, one of the few female attorneys in Reno. He described her as liberal, sympathetic to radicals, and "strong on the Negro question."

When the author needed to find employment to help finance his six-week stay, dude ranch owner Harry Drackert reluctantly agreed to hire James as a handyman at the Pyramid Lake Guest Ranch, a resort at Sutcliffe, Nevada, that catered to wealthy visitors. After about a month of unaccustomed physical labor, James was terminated, but Drackert allowed him to stay on as a lodger. James often traveled the thirty-five miles from the ranch to Reno to visit the library, the "Negro restaurant," and the drugstore where he played the slot machines.

The letters James wrote during his stay in northern Nevada shed light on both the life of an important twentieth-century intellectual and on racial conditions in Reno. Two years after his Nevada visit, the August 1950 issue of Ebony magazine showcased the story of a young woman from Richmond, California, who came to Reno for a divorce. The article "Reno Divorcee: Nuptial Knot Cut by 500 Negro Wives Annually in Divorce City" revealed an image of the city and a class of visitors whose presence in town had gone mostly unnoticed—or certainly unreported.

Confirming what had long been known, the article acknowledged that Black women were barred from the swank hotels, dude ranches, and auto courts, but welcomed at "the Negro-run boarding houses where rates are low." To be sure, African American celebrities came to Reno for divorces. Ebony noted examples such as Mrs. Bill Robinson in 1944, Mrs. Adam Clayton Powell in 1946, and the wife of Ink Spots star Bill Kenny in 1949. The majority, however, were "unpublicized West Coast wives."

The Ebony article featured a young woman named Emma Allen, who found in Reno a friendly and hospitable community of some 500 African Americans. Allen rented a room at Doris Needhams' boardinghouse on Elko Street. Needham, whose husband was an elder at the Bethel AME Church, started her business for Black divorcees because there were so few decent accommodations in the area.

While in Reno, Allen met the city's leading African American citizens. Bill Bailey, who ran the only two integrated nightspots in town, and Bethel AME's Reverend R.F. Thompson welcomed the young woman to their respective establishments. She attended a meeting of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and a social at Bethel AME. Calling itself the "Biggest Little Church in the World," Bethel AME played an important role in the social lives of Black residents and visitors alike.

The Ebony article painted Reno in a surprisingly good light. Although most restaurants held a strict segregationist policy, Allen reported that she could shop in any store in town, including "fancy fashion shops which carry the latest New York and Hollywood exclusives."

Despite the pervasiveness of discrimination, Reno's African American community embraced the divorce trade as vigorously as did white Nevadans. It functioned as a nearly invisible microcosm of the bigger divorce scene as Reno's Black population opened their homes to temporary visitors and made them welcome in a town that was not welcoming of their race.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.