Reno Divorce Colony Literature

From the 1920s through the 1960s, Reno was the divorce center of the United States. Known as the Colony, Reno attracted the famous and infamous. The literature that emerged from the Colony included informational pamphlets and brochures, magazines, newspaper articles, short stories, poems, approximately two dozen novels, and two plays. With rare exceptions, the literature was genre and pulp fiction—often no more than true confessions or anecdotal storytelling.

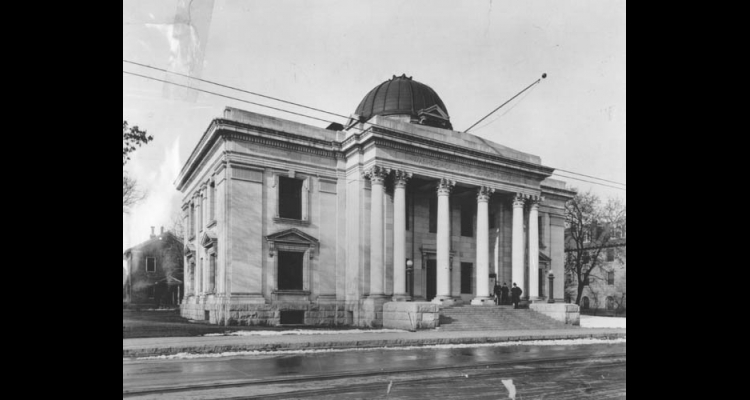

The divorce trade started at the turn of the twentieth century, and between 1929 and 1939, more than 30,000 divorces were granted in Reno. Because of this, the Washoe County Courthouse gained fame beyond its modest foundations. In 1927, when the six-month residency for citizenship was reduced to three months and, in 1931, further reduced to six weeks, eastern lawyers saw an opportunity to send clients west for divorces.

George A. Bartlett, a Reno lawyer and judge who presided over thousands of divorce cases, plays the role of sage and patriarch in his memoir Men, Women and Conflict: An Intimate Study of Love, Marriage & Divorce (1931). Bartlett renders advice on marriage, divorce and the law, nightmares, birth control, adultery, children, the rich and poor, women and business, and the price of affection. As Bartlett points out in the book, marriage and divorce are state, not federal issues, and "there are 48 different ways of getting married and divorced, geographically speaking."

A first impression of the literature is that divorce is women's work. In Reno (1941), journalist Max Miller wrote, "It is a fact that nine out of ten women who come to Reno for a divorce are doing so under order of their husbands." Although women were in the majority, men also came for divorce. Pamphlets and handbooks with hotel advertisements and sample railroad fares, such as George Bond's Six Months in Reno (1921) and Tom Gilbert's Reno! It Won't Be Long Now (1927), paved the way for what Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jr. called "the City of Broken Vows."

It helped to have money for attorney's fees, transportation, and living expenses, but the Nevada "quickie" divorce was accessible to people from all races and socio-economic levels. According to Nevada historian Mella Rothwell Harmon, "those of modest means worked their way through the three months or six weeks and found shared housing situations." While Reno accommodated all who were able to come, the wealthy got the press, publicity and, ultimately, the sordid plot lines. Anonymous articles such as "A Woman Writes: Notes on the Divorce Racket by an Ex-Wife" (Chicago Daily News, 1930); "Can Divorce Be Successful?" (Harper's Magazine, February 1938); Rita S. Halle's "The Lesson I Learned at Reno" (Good Housekeeping, April 1932); and William L. Prosser's "Divorce" (The Forum and Century Magazine, December 1938) informed readers of the experience of divorce in Reno.

Many divorce seekers, according to Harmon, "were serious-minded people who often brought their children with them and the boardinghouses and rooming houses tended to forbid fraternization." For others, the residence hotels and guest ranches created a party atmosphere. Together with time and privacy, women could indulge in flirtations and, sometimes, affairs. Other than lawyers, hotel, and guest ranch workers, these short-term residents had little contact with the permanent population. Generally, the short-lived attraction or affair with a dude ranch cowboy or lawyer ended with the divorce decree. Max Miller comments that "so many of these cast-off wives on reaching Reno, make hapless fools of themselves with strangers." This atmosphere created romantic, sensational, and sentimental plot lines, sending the message that divorce seekers were not alone.

Before air travel, the railroad was the primary method of transportation for the thousands who came to the Colony. Many of the novels started on the rails in media res. Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jr. starts his novel Reno (1929) on the Overland Limited, "two days out of Chicago" where the "easy comradeship of the West had begun." Dorothy Carman's Reno Fever (1932) also begins with a reluctant divorcee speeding on the rails toward Reno.

Where the rich and famous gathered for their divorces, journalists and writers wanting to tell or exploit their stories were not far behind. The factual bases for the divorces provided ready-made plot lines. Often the authors, such as Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jr. and Grace Hegger Lewis, who divorced writer Sinclair Lewis in Reno, were themselves divorce seekers filling time by retelling stories heard in the hotels, cafés, and bars. Journalist Leslie Curtis' Reno Reveries: Impressions of Local Life (1924) is a compilation of poems, short witticisms, and prose pieces on "Reno—the clearing house of illusion."

The novels portray women stereotypically, as anything from progressive heroines to victims who were turned out by their husbands in exchange for younger versions. Lilyan Stratton's Reno: A Book of Short Stories (1921) is a collection of "tragic little tales of the divorce colony," and an "attempt to change the world's opinion of Reno." Stratton refers to the Washoe County Courthouse in Reno as "the separator," a stout lady as a "Reno-ceros," and describes the experience of being "Reno-vated." Drago Sinclair's Divorce Trap (1931) paints Reno as a tawdry place of cynical opportunists. John Hamlin's Whirlpool of Reno (1931) describes Reno as a "heart-breaking, sophisticated little city—a Monte Carlo of the crude, raw West." Chapters titled "Secret Sin" and "Caveman Love" set the tone for this place where evenings at certain night spots were "far preferable to the grim, appalling, unpeopled silent spaces of the desert."

Lightnin' (1920), a comedic novel by Frank Bacon, adapted from the successful 1918 play by Bacon and Winchell Smith, is set in a hotel that straddles the California-Nevada state line. The story was made into a 1930 film starring Will Rogers. In 1937, socialite, editor, and writer Clare Booth Luce wrote The Women, a satirical play about a group of vindictive, superficial Park Avenue women, several of whom end up in Reno for "the cure." Luce based the story on her own divorce experience in Reno. The Women was a Broadway hit and commercial success. In the 1939 film based on the play, Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, and Rosalind Russell brought The Women to a national audience.

Leslie Ford, a pseudonym for Zenith Jones Brown, a prolific mystery writer, explored the mystery genre in Reno Rendezvous (1939). The lurid purple cover on this small-format paperback features a scantily clad blonde with a rope around her neck. "She had come to Reno to shed a few problems," says the book, but our heroine ended up with "a couple of very deadly enemies."

Faith Baldwin, a New York writer, penned Temporary Address: Reno (1941), seven stories that examine the differences between the normal versus the artificial life of Reno created by the divorce industry. Descriptive chapter titles and predictable plot lines such as "Pay for Your Freedom," "Yesterday's Heartbreak," "October Crossroads," and "I'll Never Marry!" place it in the sentimental romance genre. While many writers of the era disappeared into obscurity, Baldwin's career spanned fifty years, dozens of novels, and numerous film adaptations.

Playwright Arthur Miller's short-story "The Misfits," first published in Esquire magazine (1957), revealed a new vision of the West and the Colony. "The Misfits" is the mythic tale of the fragile, insecure divorcee, Roselyn Tabor, and the aging mustang wrangler, Gay Langford, whose cowboy lifestyle is disappearing. It is an old-fashioned love story of the death and renewal of love. The 1961 film directed by John Huston, starring Clark Gable and Marilyn Monroe, coincided with the breakup of the Miller-Monroe marriage.

The literature of the Colony is for the most part out of print. To call it literature is debatable, but its social and cultural value is significant.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.