Reno: Twentieth-Century Divorce Capital

For more than half of the twentieth century, Reno was Nevada's sin city and the divorce capital of the world. Journalists and gossip columnists called it the "Great Divide," a destination for divorce seekers who wanted to take "the cure," get "Reno-vated," and according to legend, throw their wedding rings into the Truckee River from the Virginia Street "Bridge of Sighs." A 1934 article on Nevada's divorce law in Fortune Magazine offered this description of the town: "Reno lies in Nevada's western corner, ten miles from California. Population 18,500. Elevation 4,500 feet. Reputation: bad."

Prior to the twentieth century, divorce statutes in most states were so strict that couples either chose to endure or made pilgrimages to one of the few states with more lenient laws. By the early 1900s, Arkansas, Wyoming, Idaho, and Nevada vied for the migratory divorce trade by lowering their residency requirements.

Nevada's marriage and divorce laws were established with the first territorial legislature in 1861 and carried over with little change when Nevada became a state in 1864. The residency period necessary to be a bona fide citizen was set at six months and seven grounds for divorce were allowed. Relatively minor changes were made to Nevada's divorce law through the end of the nineteenth century. Most other states in the union had far more stringent divorce laws. For example, New York allowed only one legal ground: adultery—which had to be proven in open court, and the residency period was long. South Carolina did not allow divorce at all.

Nevada's, and particularly Reno's economy had relied on the divorce trade since 1906 when the wife of William Corey, president of United States Steel Corporation, came to the city for a scandalous and much publicized divorce. A six-month residency period was mandatory at the time. By 1909, Reno had become the country's "new divorce headquarters."

The key to the rapidity with which a decree could be obtained was the satisfaction of the residency requirement. Newspaper articles promoted Reno's five hotels along with plentiful residential accommodations. In order to reap the rewards of Nevada's lenient divorce law, homeowners became eager participants in the trade by providing lodging to the temporary residents.

Following a brief and unpopular national Progressive-era attempt at lengthening the divorce residency period, America's political and social climate following World War I was ripe for the expansion of the divorce trade. The decade of remarkable national prosperity and change included open discussion of the once taboo subject of divorce. Some argued for a national divorce law while others defended a state's right to make its own rules.

Then—when it seemed that the affluence and high living of the 1920s would last indefinitely—the stock market crash on October 24, 1929 started the most devastating economic collapse in modern American history.

Nevada had long recognized the lucrative opportunities in the national debate over divorce. When boom-and-bust cycles affected its traditional economic mainstays of mining and agriculture, the legislation of sin had previously filled the gap with remarkable dependability.

In response to the economic crisis and a desire to retain the long-held title of Divorce Mecca, the Nevada legislature in 1931 passed the most lenient divorce law of any state in the Union when it reduced the residency requirement from three months to six weeks. The action cut in half the term set by legislators in 1927. It was a bold move that would carry the Silver State through the Depression in better condition than most areas of the country.

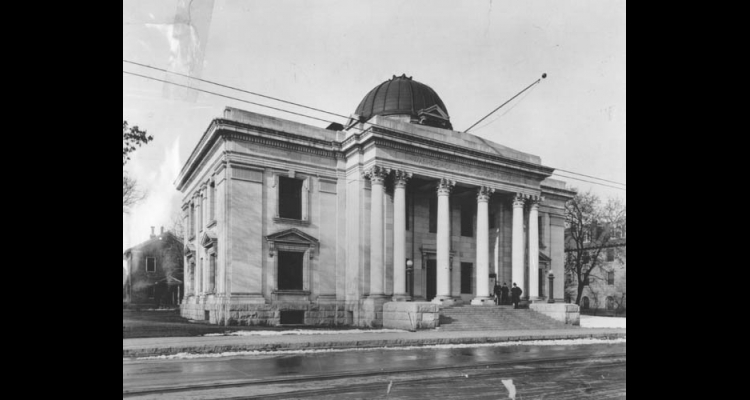

The decade of the 1930s, despite widespread economic ruin, was Reno's divorce heyday. The Biggest Little City was thrust into the American consciousness—getting a Reno divorce became a cliché. During that decade, more than 30,000 divorces were granted at the Washoe County Courthouse. Hotels, boardinghouses, divorce ranches, and private homes provided housing for divorce seekers, six weeks at a time.

The divorce trade affected Reno's permanent residents and it left a mark on the town's residential and commercial architecture. Vestiges of this vital period in the city's history can still be seen in the downtown area, in neighborhoods, and lining alleys. Both the Riverside and the El Cortez Hotel were built for the divorce trade. The owners of the home at 470 Court Street added a small cottage behind the house on Clay Street as a six-week rental. The Hiland Apartments, in the two-hundred-block of West Liberty, provided lower cost accommodations.

While some viewed Reno as decadent, it remained an enticing vision for others and a universally acknowledged destination for quick divorces until fairly recently when divorce became easier in other states. Learning that the state could profit from "sin" has been a significant revelation for Nevada—in 1931 it legalized gambling in another effort to boost the economy. Since World War II, the state has staked its livelihood on the casinos that developed and flourished on the heels of the divorce trade.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.