Riviera Hotel

Originally to be called the Casa Blanca, the Riviera hotel project languished in the early 1950s as its five partners, mostly from Miami, ran into licensing problems after the Nevada Tax Commission learned that one of its applicants had ties to the infamous mobster Meyer Lansky. In 1953, the commission approved a new set of partners, including Harpo and Gummo Marx of the Marx Brothers comedy group.

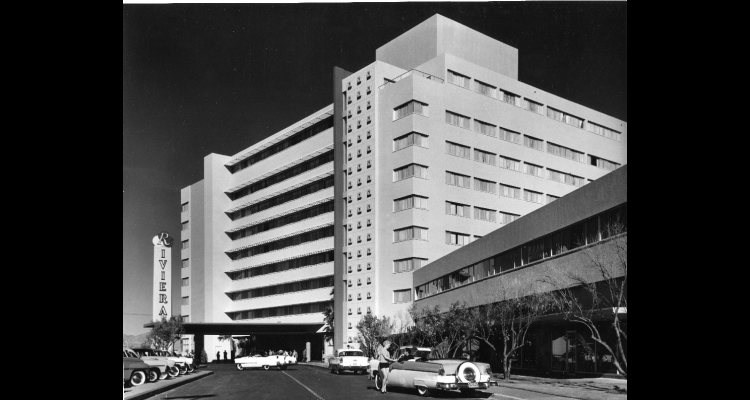

The Riviera arrived on the Las Vegas scene at the height of the Strip's postwar building boom on the Strip. Built at a cost of about $10 million, with 250 guest rooms and the largest lobby in town, the Riviera debuted on April 29, 1955, with the pop pianist Liberace performing on opening night in the Clover Room theater. Liberace, a major national star from TV appearances, was paid a then-record salary of $50,000 a week.

As a resort, the Riviera, with a fanciful décor described as "Mediterranean," provided some significant firsts for the Las Vegas Strip. At eleven stories tall, it was the Strip's first high rise, as previous hotel developers had thought—mistakenly—that the area's hard desert, caliche soil and its underground water would support only low-rise buildings. The hotel had the Strip's first elevator. It also was the first Strip resort to place one its performers (Liberace, days after the 1955 opening) on live network television, making the hotel famous throughout the country and prompting other Strip hotels to televise their entertainers to grab some national promotion.

But the Riviera struggled financially almost right away. Its investors used acquaintances, including associates of organized crime in Chicago, to approach former Flamingo Hotel executive Gus Greenbaum, considered a highly effective casino operator, to run the Riviera. Greenbaum, then living in Arizona, at first refused, but agreed later following the death of his sister-in-law, who was found murdered in Phoenix.

Greenbaum, a former bookmaker in Phoenix with long ties to organized criminals, returned to Las Vegas in summer 1955. He obtained a state gaming license after pledging that he and his partners would lease the Riviera and cover its past-due bills. He installed most of his former team from the Flamingo to manage the Riviera and share in its profits. His partners, most of them with mob associations, included "Ice Pick" Willie Alderman, Charlie "Kewpie" Rich, Davie Berman, and Ben Goffstein. Other investors included Charles Harrison and Ross Miller (the former Chicago bookmaker and father of future Nevada governor Bob Miller). Using contacts with well-heeled gamblers from his Flamingo days, Greenbaum lured many to the Riviera and turned the business around for its investors, who now included Chicago mobster Marshall Caifano.

But Greenbaum had gambling problems in Las Vegas and became addicted to heroin, which had been prescribed for him to treat his health problems. By the late 1950s, Caifano accused Greenbaum of taking more than his share of the Riviera's profits. In 1958, during a trip to Phoenix, Greenbaum and his wife were found brutally murdered. The crime was never solved.

Goffstein took over as Riviera president, but as Greenbaum's estate and some of the hotel's partners requested money for their investments, the Riviera began to run out of cash, unable to meet its expenses. In 1960, the Nevada Gaming Commission refused Goffstein's request to permit Moe Dalitz and other shareholders in the Desert Inn to invest in the Riviera.

Still, the casino survived, and recovered. In 1968, the Riviera completed an expansion project with a twelve-story hotel tower and convention facilities. That same year, Edward Torres became a major stockholder and a top casino executive. The singer Dean Martin, a member of the "Rat Pack" and a big tourist draw, received a ten percent share of the Riviera's profits in exchange for performing in its showroom.

In 1973, Meshulam Riklis, a New York multimillionaire, purchased the Riviera in a $56 million deal. Riklis used loans from the Nevada Employees Retirement System to back the hotel. He added a seventeen-floor, 300-room high rise to the Riviera in 1975 and a second, 200-room hotel tower two years later.

In the 1980s, the Riviera hosted two popular productions: "Splash," a water-based variety show, and "Crazy Girls," a sexy female revue. But the Riviera found itself with cash flow problems again in the mid-1980s. Riklis, blaming a decline in income from foreign high-rolling gamblers, filed for bankruptcy protection against his creditors. Still, he was able to back the construction of a twenty-four-story hotel tower that opened in 1988.

The Riviera expanded its gaming space, and in 1990, was also able to boast of having the largest casino in Las Vegas, with about 125,000 square feet. In the mid-1990s, the Riviera Holdings Company went public, offering shares of stock in the casino firm on Wall Street. Headed by Bill Westerman, the chairman and chief executive officer, Riviera Holdings was entertaining buyout offers for the Riviera Hotel, and a second casino owned by the company in Colorado, from various investors by the mid-2000s.

Article Locations

Related Articles

None at this time.