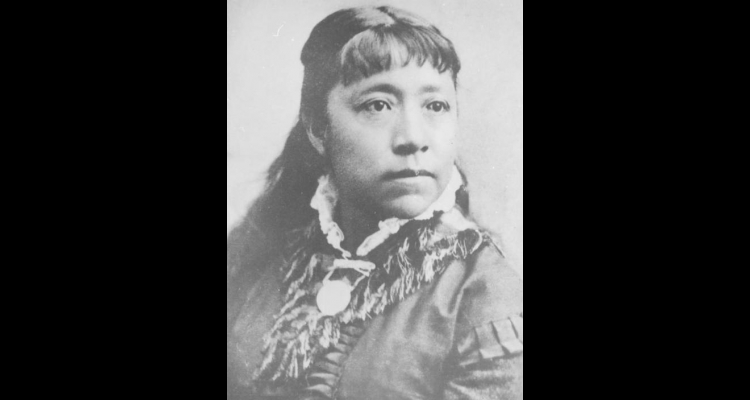

Sarah Winnemucca

Sarah Winnemucca (1844-91) was one of the most influential and charismatic American Indian women in American history. Born near the Humboldt River Sink to a legendary family of Paiute leaders, at a time when the Paiutes' homeland and way of life were increasingly threatened by the influx of white settlers, Winnemucca dedicated much of her life to working for her people.

During a period in the 1850s spent with the Hiram Scott family near Santa Cruz, and in 1857 with the William Ormsby family in Genoa, she learned the ways of the white world and mastered the eloquent, forceful English that would one day enable her to bring the Paiute cause to the nation. She became an interpreter for the U.S. Army at Camp McDermit in 1869 and later an assistant teacher at Malheur Reservation in Oregon. Meanwhile, she underwent vicissitudes in her private life with several failed relationships.

When the Bannock War broke out in 1878, she served the army as scout, messenger, interpreter, and close associate of commanding General Oliver Howard. She secretly led her father's band to safety from the enemy camp. Winnemucca's bravery in the face of great danger and her epic rides for long distances over harsh terrain are the stuff of western legend. At other times, she served peace as vigorously as she rode her galloping horse across the deserts with a general's message.

After the war, all the Paiutes who had deserted Malheur Reservation were exiled to Yakama reservation, whether they had participated in the war or not. This was a cruel and unjust punishment imposed in violation of commitments made to the Paiutes. So many Paiutes died from the diseases prevalent at Yakama that they overflowed the graveyard, and the reservation agent ordered their bodies thrown in the Columbia River; so strong were their ties to their homeland that they thought of nothing but returning to Nevada. Winnemucca made every effort to get them there. She lectured in San Francisco on their plight to arouse public opinion. She traveled to Washington, D.C. with her father, brother and one of the Paiute headmen to appeal to Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz and the president to win their release. With Schurz's written promise that the Paiutes might return home in hand, Winnemucca made another of her epic rides through snow and danger to bring it to Yakama, only to see Schurz change his mind. His were "promises which, like the wind, were heard no more," she bitterly observed. Evicted from the reservations, Winnemucca, from a place nearby, counseled her people to undertake a program of passive resistance. Refuse to farm, she told them; build no houses, do nothing to indicate that you will accept staying at Yakama. Gradually, the Paiutes succeeded in escaping in small groups.

Once Winnemucca promised the Paiutes that she would work for them "while there was life in my body"—and so she did. She personally brought the Paiute cause to secretaries of the Interior, army officers, legislators, and senators. She testified before Congress. She appealed to public opinion through interviews, newspaper statements and her many impassioned lectures in theaters, churches, and parlors on both coasts severely criticizing the reservation system: "I pray of you, I implore of you, I beseech of you, hear our pitiful cry to you, sweep away the agency system." In 1883, she took the Northeast by storm, lecturing more than 300 times, always spontaneously.

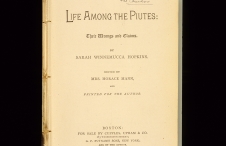

In 1883, while staying at the Boston home of her friend and supporter Elizabeth Peabody, Winnemucca wrote her autobiography, Life among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims. She combined the history of her tribe and a description of their culture with her own story and several letters from her supporters. It was the first book written by an American Indian woman, the first by a Native American west of the Rockies, and the first to describe Paiute culture. Peabody's expertise in publishing assured its publication, and few books have lasted as well. Today it is once more in print, often read, frequently cited by historians, and carefully analyzed by literary scholars.

In 1885, Sarah started an American Indian school, funded by private donations, on her brother Natches' ranch near Lovelock, and created a model for Native American education that was far ahead of its time. U.S. policy in that era aimed to eradicate Indian culture and "civilize" the Indian, as officials called it, by "education for extinction," in the telling phrase of historian David Adams. Conversion to Christianity was the keystone, and the minds and hearts of the young were the battleground. They were to be assimilated in boarding schools, preferably far removed from tribal culture, until all that was Indian in them died. What was being done to American Indian children and their families makes heart-breaking reading.

Reservations agents scoured the hills where Indians hid their children, threatened Indian mothers with losing the family rations and jailed stubborn fathers. Winnemucca refused to allow boarding school officials to take any of her pupils without the consent of their parents and strongly stated her opinions. She told the press that the right place to teach children was in their homeland amid familiar surroundings, with their parents nearby, not among strangers in a distant land. Although she firmly believed that "education has done it all," she never favored the eradication of Paiute culture, only the adoption of some of the innovations that had given the white man his power, such as writing. In the Paiute way, Winnemucca taught with kindness, her pupils responded eagerly and punishment was unnecessary. Yet unfortunately, her school lasted no more than four years due to lack of funding.

Another factor working against the school was the effect of Wovoka, the Ghost Dance messiah, who preached that the American Indian dead would return to life and the world would be restored to the Indians if the believers did the Ghost Dance correctly. Sarah called this prediction "nonsense." All her life she had walked the rational path laid out for her by her beloved and influential grandfather, Truckee. If her people were to prosper in the white dominated world that had been forced upon them, they must learn practical skills, not wrap themselves in dreams, she believed.

After her school closed, Winnemucca went to live with her younger sister, Elma, at Henry's Lake, Idaho, where she died under mysterious circumstances in 1891. Sarah had not achieved all her aims, but she had accomplished a great deal. As tribal elder Majorie Dupee has said, Winnemucca's brave life helps us "hold to our pride." Nevadans widely share her pride in this heroic American Indian woman. In 2005, a statue of Sarah Winnemucca, representing Nevada, was unveiled in U.S. Capitol Statuary Hall, Washington D.C.